The Freedom to Recognize a Face

Some thoughts on Leon Kossoff's early portraits

Start with a face.

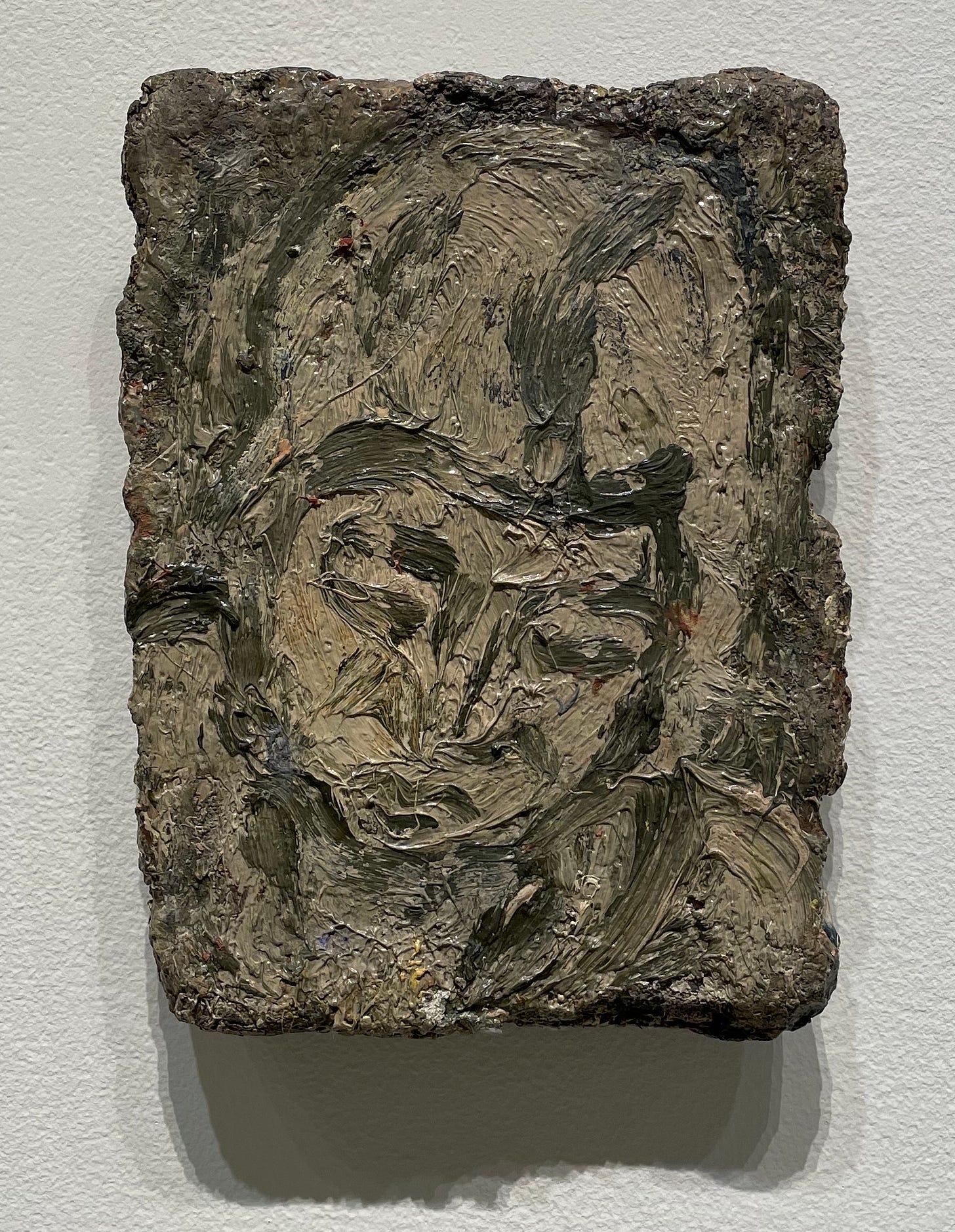

A small oil on board, upon which the paint has been brushed in repeated campaigns. Excess paint exceeds the edges of the board, giving the whole a fragmentary appearance, as if it was a shard of gessoed plaster, or even a knobby slate. Everything happens on top of this, but is also embedded in this. The edges are roughed up – the word that comes to mind is “accreted”, like the molten rock that aggregates and darkens as it cools at the edge of a lava flow.

The head is bowed, the shoulders canted to the left, sloping left, as if turning. The forehead is defined by two swipes of taupe. Another swipe divides the crown of the head, dirty beige on either side. The eyebrows are prominent, as are the shadows beneath – though it’s not clear they are shadows. Each eye is a one/two beat of dark and light striping, a pattern more than shape, but a pattern without integrity; not knots then, but maybe not exactly vortexes either.1 Whatever form there is of a nose is difficult to discern. The paint here is thick and liquid. Cordy. The lips and chin overlap, are indistinguishable, or maybe just the lips define that jut of the jaw.

At the neck there is just a dash of yellow, which looks to have been accidentally brushed on to the squelch of beige below it. There’s an accident of white too, and an even smaller one of blue in the same area. The white comes from below. The blue is a settlement on top, and perhaps is a continuation of another wipe at the edge of the face’s right cheek (it lines up with a right-handed down stroke that roughly defines the nasolabial fold).

There are two times, or two temporalities, at work here. One can be identified with the edges, or the margins; and the other with the face or figure. As noted, the margins and edges appear as accretions, build-ups of paint, of repeated additions and layerings, of things hidden below the surface. This is most evident at the top edge, and in the “empty” corners at right and left that rise toward the viewer, which give one the sense that this portrait is a depression, a pooling. This is the other temporality: the traces not of the paint’s mere liquidity, but its viscosity: “the state of being thick, sticky, and semifluid in consistency, due to internal friction.” Each stroke is a one-time mark, but dilated, so that direction, pressure, dynamics can be, if not known, at least guessed at.

We are born to recognize faces. But by 1969 Leon Kossoff had worked on a number of portraits in which the faces never cohere (bodies, as figures, are easier to read, because more abstract to begin with). His Seated Woman (1957) is a good example. Self Portrait No. 1 from 1965 may be a better one. In this work, one can strain to make Kossoff’s or any face appear, but it would just be an affirmation of one’s own credulity, akin to seeing Jesus in a water stain or a slice of burnt toast.2

One might be tempted to say that the faces in such early works have been “obliterated,” but the sense of erasure or of wiping-out which “to obliterate” entails also suggests that there was a face there to begin with. The facial gestures in these works reach for legibility; they don’t disable it.

But in that reaching they rarely gain hold, save in these faces’ relational placement within the generic pattern of a body. And when there is no body, as in the Self-Portrait from ’65, we’re taking the artist at his word.

In these works Kossoff is indulging in the excesses of the paint itself, and playing with, or experimenting with, its capacity to signal or signify something other than itself, even as it signals and signifies its own identity as paint. It’s almost as if, in drawing the paint up into three dimensions, in working in this sticky, viscous relief, Kossoff is attempting to draw out not just an image, but something of painting’s history and capacity for image-making, and thus meaning-making, but also (and this may be an indulgence) something like its capacity for autonomy or “freedom-making” (more on this in a moment).

That faces would present the sites upon which this attempt is made most dramatically stands to reason, insofar as faces are sine qua non sites of recognition. Not sites where recognition happens, but really the conditions of possibility for recognition itself. The evolutionary psychology on this subject goes a long way to demonstrating how evolution has selected for this recognitive trait and made it innate in humans. Mirror neurons and the like have helped us understand how our own neural architecture is shaped and conditioned by our seeing others and so seeing ourselves in others. Our selfhood is always already otherhood, and vice versa.3

But understanding this does not get us very far in thinking about why or how Kossoff, who was engaged in an artistic project of and about representation, during an epoch when painting’s ability to “represent” had been subject to consistent questioning – to the point of something like an enduring crisis of representation going on a human lifetime – would be engaged with faces (but of course not just faces) in the manner that he was in the 1950s and ’60s, and why or how that engagement changes between Self Portrait No. 1 from 1965 and Small Head of Peggy from 1969.

Whatever the nature of that engagement, be it problem or opportunity, it’s evident that things were changing quickly in 1969. Nude on a Red Bed, Summer from the same year evinces a completely different facial treatment, one echoed in Small Head of Rosalind No. 1 (1970). In these works, the linearity of the paint stroke is being put to work to define the facial features – eyes, nose, lips, brows – and without ambiguity. The dichotomy of (dark) line and (light) colorfield marks a turn to drawing that stands in stark contrast to the works of the prior decades, in which the only “drawing” on offer is the drawing-up and drawing-out of the paint itself, as if what Kossoff is up to is trying to catch, or lure, or gain hold or possession of something that painting (and only painting) could do for him. (It’s also equally possible to think of Kossoff’s work of drawing painting up and out of itself in these years not just as an attempt at possession but also as a letting go, a relinquishing of some kind of pictorial burden, which opens onto a less fraught relationship to the practice and status of painting itself. Call this the catch and release theory.)

It seems necessary to acknowledge that this business about faces was very much on the agenda in 1960s intellectual and artistic circles in Europe. Emmanuel Levinas in particular made one’s “face-to-face” relation to the “other” and the responsibility (the “demand”) that this relation entails the cornerstone of an ethics that seemed to speak directly to the decolonial wave of independence movements that swept across that decade. As tempting as it might be to look to Levinas to help contend with Kossoff’s treatment of the “face,” however, Kossoff, at least in this period, is not taking the faces of his subjects as a given (as Levinas would require). Kossoff appears to be working through a different, or prior problem, which as noted above has to do with the face as a site, if not the site, of recognition.

I don’t want to belabor this point underneath too heavy a theoretical burden, but it does seem (I want to say “on the face of it” here) that the face in Kossoff’s work of this period is a privileged site where the viewer is challenged to see even the categorical notion of a “face” in the artist’s portrait subjects. By “categorical notion” I mean even just the basics of a pattern of standard features (eyes, nose, mouth) on a quasi two-dimensional plane that are legible as a “face.”

This two-dimensional piece is important, insofar as its signals a distinction from the category of a “head”: the features of a face, in order to be features of a face, must have the capacity to be visible all at once (it’s why we don’t conventionally speak of a horse’s “face,” just “horse heads”). It’s also why the face as site of recognition is a particularly charged site for painting, whereas head is a particularly charged site for sculpture; just think of Brancusi.

I also don’t want to suggest that the face was somehow Kossoff’s singular or even primary concern. Figures and landscapes were obviously equally important subjects for his practice, and no doubt many of the same representational challenges that Kossoff was contending with and which I am working out here could be productively thought through with an eye to his other canvases. But to look at the face in Seated Woman (1957), and to the portraits of Kossoff’s father and mother from the early 1960s, and at his first self-portrait, and then to look at the transformation at work in Small Head of Peggy, demonstrates that the depiction and handling of faces, that Kossoff’s handling of paint to depict faces, presented a challenge that Kossoff was indeed working through (again, amongst other things).

That challenge should not be confused with Kossoff’s grasping at some as yet unachieved technical facility for mimetic representation. Though the young Kossoff did fail to get into the legendary St. Martin’s School of Art in the late 1940s because his drawing skills supposedly weren’t up to par, we can take it as a given that Kossoff could draw a face. And in fact the simplicity of the “drawn” faces that arrive in the portraits after 1969 demonstrate that just getting to something that could be recognizable as a face, let alone recognized as a specific face, was after that date no longer a significant issue in Kossoff’s portraits. One could get stuck on the St. Martin’s biographical detail, and suggest that his early works from the 1950s were directed against something like drawing itself – a pitting of drawing (with its linearity, its flatness, its subservience to illustration) against painting (with its capacity for relief, and layering, and fields of free sensation) – because drawing was to blame for his rejection, and so he would reject it. But that rejection sent him to tutelage by David Bomberg (another art school reject), and by 1953 he was studying at the Royal College of Art. Kossoff’s work from this period is surely more than simply a grudge worked out in paint.

Importantly, the subjects of Kossoff’s portraits during this period were often the people closest to him – his mother and father, his wife, a distant relative, but one who posed for him regularly. Their features were no doubt some of the most well known to him. Which is not to say that they should be or could have been easily represented by him. It’s only to note that these people were intimates of Kossoff’s, people whose faces were part of a family milieu, where their “otherness” would need to be understood within the narrative of his childhood development, with all of its attendant familial interpersonal relationships, and the growing subjecthood that comes from family and extended kin relations. These relationships, because primary (as in, the first ones that any of us are ever involved in), often serve as the models for the interpersonal relations that we, as individuals, develop more or less successfully as we move into and then through the wider world.

Yet it is exactly these portraits, of these people, in which we encounter Kossoff wrestling with the recognizability of his subjects as subjects, ones that might fail to be recognized by others as even generic subjects – i.e. not specific people, but people nonetheless – given how they are handled. By the time of Small Head of Peggy, however, Kossoff has made a move to make such recognition easier, simpler, more straightforward. There is indeed a face here, and so a person (for sure!), which any viewer would recognize as such. Whereas in the self-portrait from 1965, as much as we might want to see the artist there, or anything resembling a person, that basic or baseline level of recognition would have to be characterized as a stretch at best.

So by the time of Small Head of Peggy we have to conclude that Kossoff is interested in, or is taking account of, or is at the least acknowledging, such recognitive capacities as important to his developing painting project. We could go further and say that, up to the time of Small Head of Peggy, Kossoff was engaged in a portraiture practice, in the representation of other subjects, which was Kossoff’s alone, and which was being worked out on subjects whose status as subjects, because of their proximity and intimacy to Kossoff, could be and were taken for granted (at least by the artist). With Small Head of Peggy, that work of drawing-up some semblance of a figure which is at the same time a drawing-out-of-paint a figure with a recognizable face, one that could be recognized as such by others, if even minimally, marks an important shift in his practice.

Kossoff’s painting at this point then takes on something like a social dimension. In opening up to this recognition by others, Kossoff was moving beyond the merely individualized expression of his own artistic agency, his own “expressionism,” and towards something more mutual, more accepting of outward determination by the conditions in which he found himself. Whatever one wants to identify as those conditions – family (Peggy), neighborhood (Willesden street scenes), city (London Underground stations), landscape (after Poussin), history (the Sixties), etc. – doesn’t really matter on this point, though they certainly do matter to Kossoff’s later practice. What is important is that Kossoff, on the evidence of the work, came to a realization that his painting practice could not continue to count fully as his own until it also counted for something like “portraiture,” or “painting,” or even for “art” in general, at least as these ideas were determined by his time.

What is interesting is that, by exactly this time, the recognizability of art as such, at least as it had been historically determined to this point, was undergoing a radical expansion as to what could count as art. The decade of the 1960s saw the apotheosis of modernist art, as well as this art’s alignment with a fully articulated theory of modernism,4 and at the same time it saw a concomitant assault (by the likes of conceptual, minimal, and pop art) on the artistic norms and practices out of which, or on the foundations of which, that art and its discourse had been forged.

What Kossoff was doing as a painter, then, in order for it to achieve some measure of autonomy as a free and meaningful act of painting, was not something that he could accept as a simple assertion of his own agency. It was not enough to simply state, as if in paint, “This is my self-portrait if I say so,” a gesture that was on offer at least since 1961 when Robert Rauschenberg made a portrait of Iris Clert in exactly these terms. In order for Kossoff’s painting to achieve that autonomy, in order for him to get past the “internal friction” of this viscous stuff, he needed to make “recognition” the underlying thematic, or the operator, of his work, which is why Kossoff’s faces, at least up to and including Small Head of Peggy are privileged sites for understanding and seeing this thematic of recognition at work.

This is what I meant earlier by the “freedom-making” aspect of Kossoff’s painting. Freedom requires, is contingent upon, a mutuality of freely given, uncompelled, and unchallenged recognition. It can be asserted, even demanded, but it cannot be fully realized without recognition from without. It is in Small Head of Peggy that a face is drawn-up and out of paint, not to represent “Peggy”, but to give us a small measure of freedom, in recognition.

Leon Kossoff: A Life in Painting opens at L.A. Louver in Venice, CA, on January 26 and is a continuation of exhibitions at Annely Juda Fine Art, London and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York. For the essay and arguments above I have drawn exclusively on the works on view and in the catalogue for the exhibition. There are others that could be substituted for those named above, and there are certain works that certainly work against the arguments I’m putting forward on the basis of Small Head of Peggy, but then again, there are other works not mentioned which do equally as much to support them. I am not a Kossoff scholar, as will be evident to anyone who is. Nor do I have the time or intention of becoming one. The words above are just a working out of some ideas that came to mind when I had the good fortune of seeing the show in the good company of my own daughter. Take them or leave them as you will.

The terms are Hugh Kenner’s. His muses are R. Buckminster Fuller and Ezra Pound. See Kenner’s The Pound Era (University of California Press, 1971).

In the 1960s this recognitive condition was being rewritten as fundamentally alienating, most notably in the orthodoxies of existentialism and psychoanalysis. As will be evident, the recognition at work in Kossoff’s work is doing something different.

Clement Greenberg’s influence dates to the publication of Art and Culture in 1961, even though some of the seminal essays published in that collection date to the late 1930s. As an artist friend once told me, everyone had a copy of Greenberg’s book in their back pocket in those years.