Some Art in San Francisco Part 5

Mattea Perrotta and Nick Gorham @ Et al; Adrian Kay Wong @ Hashimoto Contemporary; Marta Thoma Hall @ Anglim/Trimble; Wendel A. White @ Rena Bransten

Nick Gorham and Mattea Perrotta at Et Al

My friend and colleague Chris Sharp wrote a position piece in 2017 about the need to find and support what he called “minor” work, which is an idea that is hard to pin down, and is better understood in terms of what it is not. To that end, Sharp wrote:

The major reduces and recuperates, streamlines, flattens out, absorbs, and eliminates difference. Art is never an end in itself, but a means, a vehicle. Seeking the lowest common denominator, which is often found in either spectacle, topicality, or use value, it continually asks what art can do, as opposed to what it is or can be, which it almost always takes for granted.

In this, major art is often grandiose, flashy, and expensive (both to make and to buy); it can be overly serious or overly knowing; it can be seen performing its intelligence rather than being intelligent, and it is often disdainful of its audience, even as it seeks out, because secretly desires, its audience’s approval.

As with everything made in modernity, including ourselves, sincerity is often bought cheap and sold dear. If a “major” work of art can be seen to be sincere about its “major”-ness (think Maurizio Cattalan, or Matthew Barney), then it can often be quite good, or at least entertaining. If it is cynical about that major-ness, then it’s often neither (think Stefan Brüggemann, who will forever be the bogeyman of cynical major-ness here). The minor must be given equal treatment nevertheless. Of minor works, we have to acknowledge those that are cynically minor, and those that are so sincerely.

It is surely in both Nick Gorham’s and Mattea Perrotta’s favors that their work could be seen as minor; it is however a problem for them that this question of sincerity versus cynicism remains undecided.

Take the case of Perrotta first, who has produced a suite of very small, heavily worked and heavily painted compositions, all unique and irregular to a point, all of which seem to want to assert nothing so much as just this: their size and their having-been-made-ness.

The question is why? If the answer is because to seek an art of ambition, a project with some purchase on both history and our present, with something to say about what painting can be in 2025, something that makes a tacit claim as to what painting might be next year and for years after that — if to seek for something like this seems foreclosed, or too affirmative of contemporary culture, with all of its political disappointments and apocalyptic forecasts, and so let’s make just these small things, which don’t take up too much room, won’t step on anyone’s toes — hell you can even fit them in a carry on, which soothes the logistics heartburn (but won’t do anything to cool the climate) — these things that speak only of the artist’s labors, a certain apprenticeship to materials, a commitment to making no single picture too appealing, too composed, too pretty — well then intentionally or not we’re slipping on the scree of the cynically minor.

Sometimes a sincere act is unaware of its cynical positioning — how else to describe the “post-growth” movement? — and Perrotta’s works are too on the nose not to hazard the conclusion that they are, when taken together (as they must be), a pose of this type — too concerned about the present or anxious about the future to want to exceed it. This isn’t for me; and it shouldn’t be for you either.

Gorham’s work is different. Here is the case I will make for it. This work is sincere in its dealing with the problem of the edge — not the edge of the stretcher or the shape of the canvas, but the bounds between shapes. And what seems relevant to Gorham’s paintings is not that edges are what make shapes what they are (no edge, no shape — yes, there’s a whole “pareragonal” aporia here that was almost too boring forty-five years ago when it kept a certain kind of formalism on life support), but that shapes for Gorham are an excuse to work on this problem of edging.1

I think this explains why Gorham’s compositions and color palettes and experiments with facture and collage are not particularly compelling, except as ways of charging and pressuring the appearance of the edge as an organizing concept in the work. Another way to say this is that the compositions, as compositions, don’t hold any interest, appear largely arbitrary, but carry enough of the scent of Serge Poliakoff (with hints of Delaunay and Schwitters) to smell like the rotting corpse of modernism, a scent that people still seem to love. If Duchamp could call painting after Seurat and Kandinsky nothing but “olfactory masturbation,” then to continue to prop it up today with talk of color and composition is something closer to necrophilia.

But don’t take my word for it. Gorham is saved from the graveyard by none other than David Salle:

The primary difference between painting and digital images, between things that are made and things that just are, resides in the edge. In the digital sphere, an edge – the boundary between two or more forms – is just pixels. Edges do not constitute an event because the whole image is just pixels. Every square inch reads with the same undifferentiated, uninflected detachment, which can sometimes be the source of its charm, but more often makes me want to throw something at it. In painting, the boundary between two forms is fraught with meaning; an edge is the result of a gesture, a decisive action. The way a painter handles edges plays a large part in defining his or her style. What we call ‘style’ is the sum total of all the decisions taken within a work of art combined with a physical capability, or talent.

Put to the side for the moment that Salle here makes the same category mistake that other defenders of “Art” against AI make, which is to believe that style, by which Salle really means the artist’s “intention,” is a function of a the “sum total of all the decisions taken within a work of art.”2 Salle articulates exactly what it is that makes what Gorham is doing relevant.

Now, whether Gorham thinks this is the context in which he is working and is himself intentional about it, whether he would explain his project in just these terms, as one of exploring the condition of the edge as the condition that divides painting from image making — acknowledging that the latter is something that machines can do and is increasingly their province — is a good question, but perhaps largely irrelevant. It is manifestly what the paintings are about. And the problem of the edge, which is the negative problem of the image, is, on the face of it, what Gorham is dealing with, sincerely.

Adrian Kay Wong at Hashimoto Contemporary

Wong makes works that sophisticates are inclined to dislike: flat, graphic, and illustrational; they reproduce well (really well), they’re vaguely narrative, they’re (too) quickly conscripted into conversations about generational malaise or anomie; there is a subtle but at the same time emphatic identitarianism and regionalism about them; “quiet” “still” “intimate” — the clichés gather on the tongue like milk scum from too-hot tea.

And yet, there is something interesting going on here. Wong seems hyper aware of the reduced-dimensional conditions with which painting needs to contend (reduced in terms of discourse and in terms of form if not content) and so he has tried to make this, in some respect, what the work is about. In a world so dominated by and determined by image, the icon of reduced-dimensionality, Wong makes the world — his world, the world of his paintings — about screens and screening.

The way to see this is to see how everything is frames and crops: windows, mirrors, siding, pictures, doorways, drawers, posters, blinds, fishtanks, and yes, the occasional smartphone or laptop or monitor — everything is a device for “screening” and “screening out” elements of the picture via elaborate hide-and-reveal stagings. The people, the flowers, the views out the windows, what are these if not just nods to historical convention, the “legacy” media of Portrait, Still Life, and Landscape that have become nothing but generic in a world of flattened content — the stuff that appears on screens, the stuff that gets centered and marginalized, cropped-in and cropped-out. These are scenes that are not scenic, even if they remain rewarding to look at.

That Wong has gone so far to present his work on, or as, an actual folding screen, only brings this point home. It also demonstrates that Wong is self-conscious of contemporary art’s, in particular contemporary painting’s, need to deal with the problem of the decorative — how could he not be given how his paintings are so often partial views into, if not fully of, interiors.

And yes, you could say this thematizes or implicates the withheld interiorites of his “characters,” whom we never fully see, who are never fully “pictured,” and that this has something to say about their withholding of themselves, that — if entertaining this line of thought — they are present to themselves only in these fragments of the world they surround themselves with, fragments that can never promise some kind of plenitude or fullness, which is why they are so often pictured at windows and doorways or on stairways, stuck on some threshold, between what one must believe are their existential conditions of alienation and some kind of true agency or freedom that is just in the offing…

But then, provided you’re still awake, you would just be buying what the picture is selling, and not thinking of what it is about.

Marta Thoma Hall at Anglim/Trimble

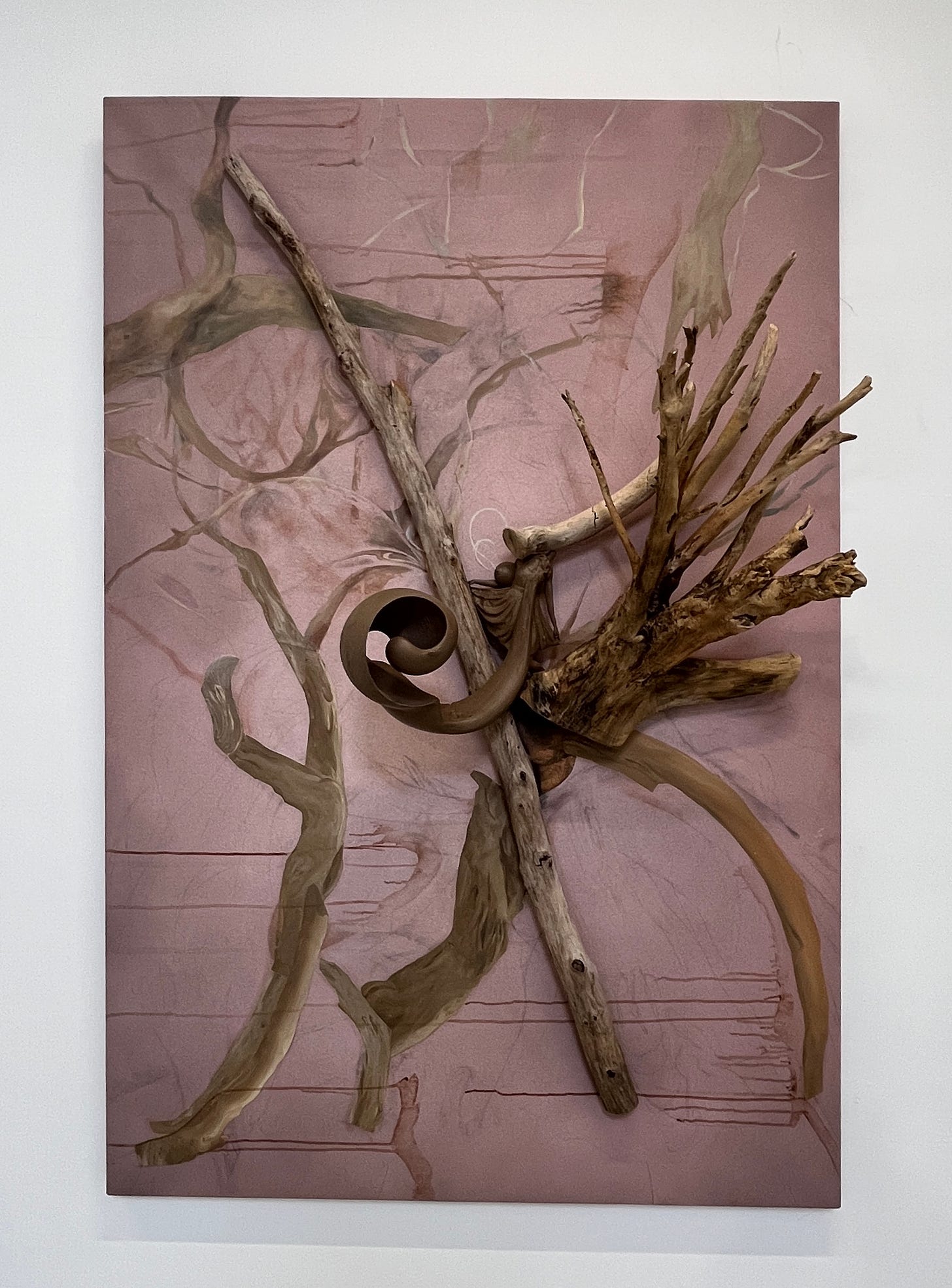

I’m tempted to characterize Marta Thoma Hall’s works as what it would look like to witness painting undergoing what today gets called a “mental health crisis” but not so long ago was described as a plain old “nervous breakdown,” which is more descriptive and gets at the form problems in the work and why they might be there. To be clear, this is not a denigration.

The works are frenetic and all over the place, but in a very specific kind of way: Hall uses 3D printed elements, such as contorted horse figurines and tumorous driftwood, along with other found objects, such as seashells, as pendants to the pictures, and the paintings themselves may consist of heavy impasto as much as thinly painted cartoon-type graphics or lightly drawn line figures. There remains a baseline coherence. The mind here might be disturbed, but it’s still conscious. References and styles abound: there are strained attempts at Tiepolo skies, bits of expressionism, some derivative Max Ernst, and so on. But to follow those flights of fancy is for shrinks who want to pad their hours.

There’s no sense to any of it (which may be a strength? I can’t tell). It’s as if Hall, faced with the new technologies of image and form-making (from AI to rapid-prototyping), wants to advance the practice of painting but can only do so by not thinking about it. And no matter how much one wants to enlist the “unconscious” or “intuition” or the “spiritual” in support of what Hall does and what one might see in the work, it’s all just another way of talking about work that has lost its mind.

Selections from Wendel A. White’s “Manifest” at Rena Bransten

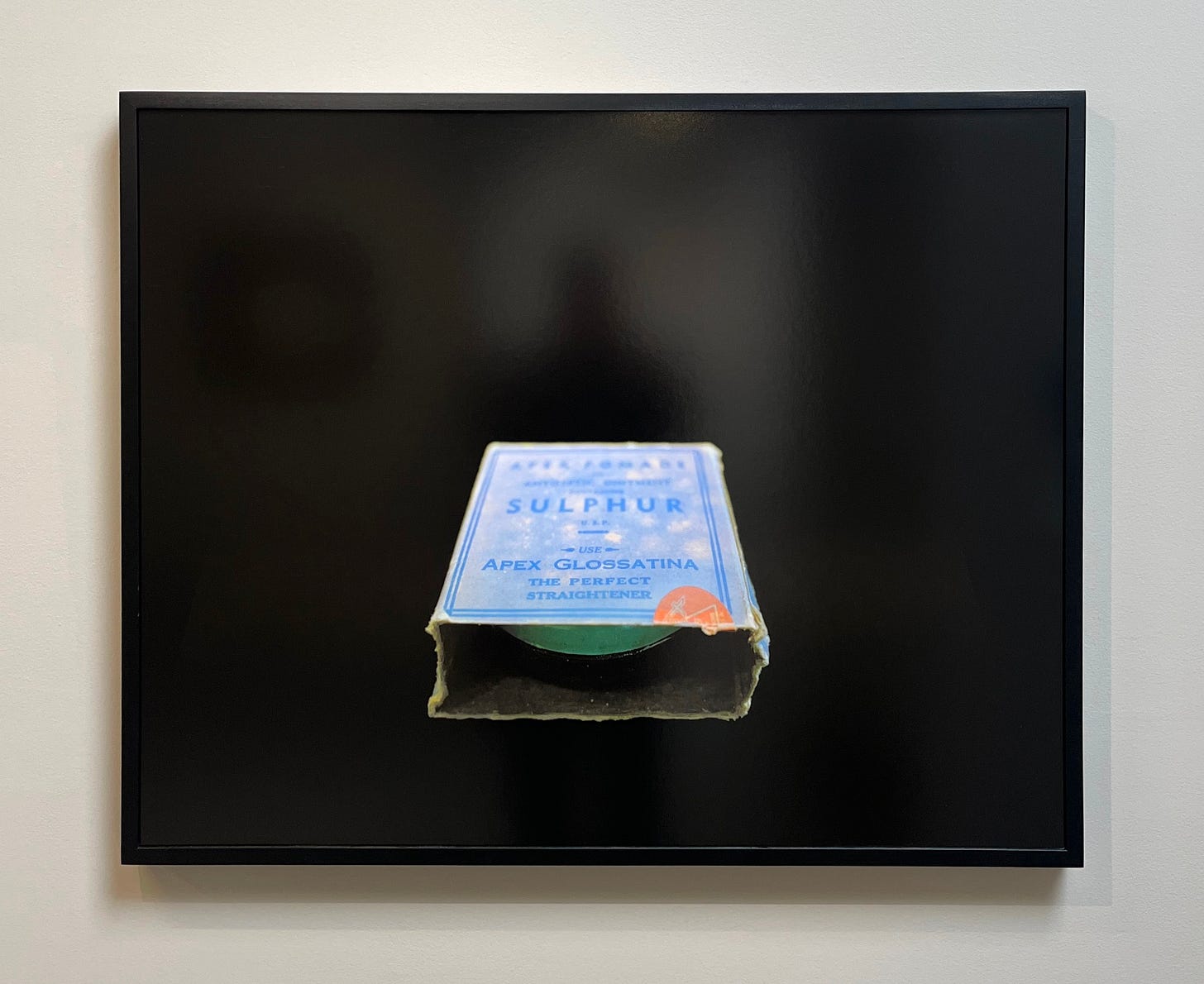

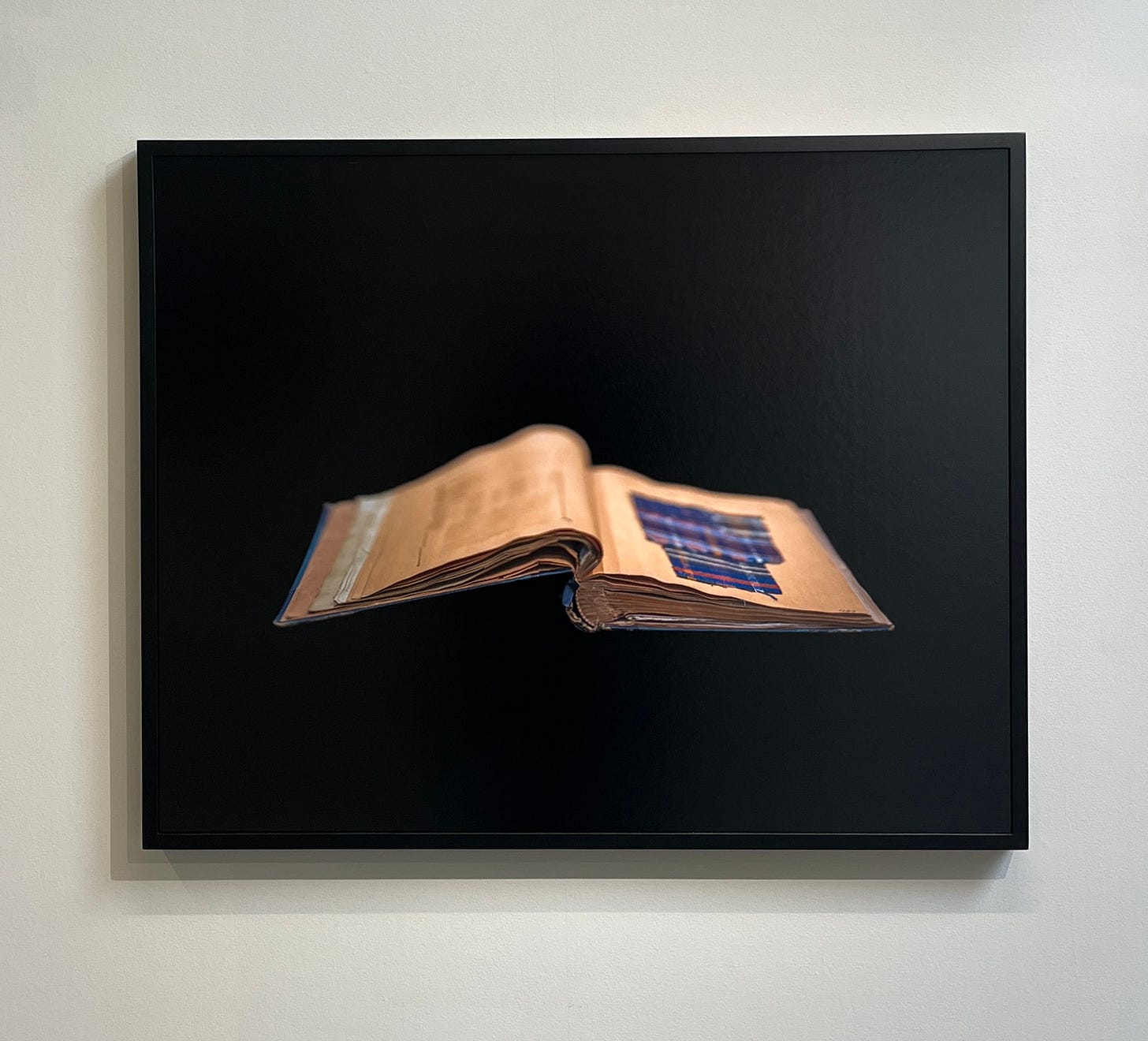

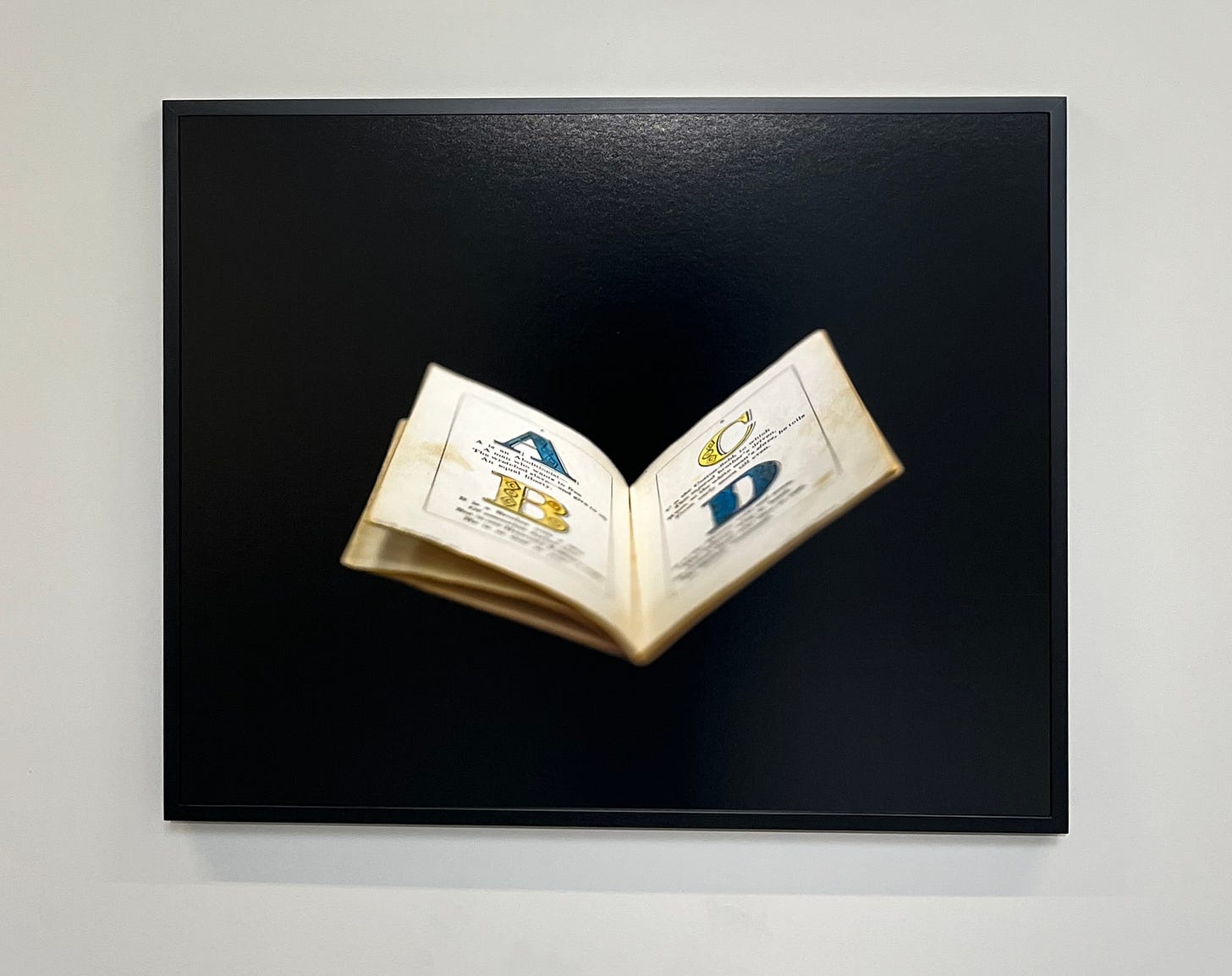

“Manifest” is the title of Wendel A. White’s more-than-decade-long project of photographing the material culture of black history in the United States. It’s an impressive project, much of which has been recently gathered into a book co-published with the Peabody Museum at Harvard. The photographs are uniform in their manner of presentation: the objects of White’s attention are presented against an eggshell black background that occludes any context (no tabletop, no backdrop, no surround) and often receding from the camera when captured with the shallowest depth of field, meaning that some portion of the artifact (forward edge, rear dimension) is out of focus. As White explains it:

I am not trying to create a descriptive catalog of the objects in the way that would be useful for a library database (always clear and highly detailed, descriptive photographs). The result is that my photographs are often (not always) narrowly focused on a particular detail of the objects and in many cases the most descriptive aspect of the content is obscured (a metaphor for public attention to Black history).

I know this is White talking about his own work, but forgive me if I find this metaphorical reading of his own formal technique somewhat tendentious. How would this metaphor make sense of the acute focus on other areas of the object? Would that be an indictment or an affirmation of the connoisseur’s view? The conservationist’s? The photographer’s? Of course it’s undecidable, because this metaphor just doesn’t do any real work. In some photographs, informative details are willfully obscured, in others they are kept wholly legible, still in others there is no “information” (writing, label, image) to glean. This is all to the good, not because the logic, whatever it might be, is inscrutable, but because White’s project is simply more interesting than a one-liner about public interest (or a purported lack thereof) in black history.

It’s frustrating, however, that this work, which is anything but illustrative, is written about almost always and at every turn as simply illustrating its content. It does not detract from the stories the objects themselves have to tell if one choses to attend to the images and how they work; nor should it be taken as indicative of a specific (racial, let alone racist) politics if an attention to form — how the photograph appears — is considered equally if not more relevant than an attention to its contents.

The work is rich enough and strong enough to warrant a range of takes that exceed the all-too-limited frame through which it is so often seen and written about. If we take White at his word (and we should) that he is not creating “descriptive photographs” of the kind one would find in a library or other archival database, then it’s worth asking, what kind of photographs are these?

Manifest has its roots in a more conventional documentary series called Small Towns, Black Lives (1989-2002), which White describes as “predominantly portraiture.” Which leads one to ask: Isn’t Manifest too a portraiture project? And if considered in these terms, wouldn’t that unlock an entirely different way of thinking about what these images are doing and how they are doing it? Consider that Manifest’s origin story begins with White’s finding in the special collections at the University of Rochester a lock of Frederick Douglass’s hair and the first book the famed abolitionist owned once free of slavery — some of the first objects that are pictured in Manifest. Even the most superficial accounts of Douglass’s relationship to photography — that he was the most photographed subject of the 19th century, which means the most ubiquitous portrait subject — suggest portraiture as a productive direction of inquiry for this work.

But Douglass’s lock of hair and book are interesting in a different direction too, as they suggest two different models of representation, two ways that material things in the modern age gain and hold their value. One is by being relics, which bear physical traces of the people or the places that invest them with import; the other is by being icons, whose import is derived from their being recognizable —through the repetition of resemblance — as the object or image that they are.

Many of the most interesting entries in White’s Manifest have the virtue of operating on both of these models (just as all photography does). The shallow depth of field reveals, in high relief, the reliquary character of White’s chosen artifacts, their having been used and handled, their bearing the traces of certain people’s and certain places’ impingements on their surfaces, not their histories per se (these objects cannot speak for themselves), but that they have a history.

At the same time, that shallow depth of field ensures that some aspect of the artifact is blurred, that its reliquary guarantee of a unique history cannot be taken as the whole or the only story. Here the artifacts function as icons, recognizable as tokens of larger networks of communication and commerce (books, pictures, radios, files, consumables), which is how White’s photographs function as well, retrieving their subjects from dusty archival storage boxes and drawers and returning them to circulation, to transmission, to view, as images.

To see White’s Manifest photographs operating as both relics and icons is again to see them as photographs, as contributions to a conversation about what photography is, and how it operates, especially at at time when photography itself, the historical and theoretical idea of it, has become, or is becoming (in its way) obsolete.

This is not explicitly about sex, but one can’t rule it out.

Ted Chiang and Neal Stephenson have made exactly this “sum of decisions” argument in their defense of human creativity against whatever it is we think machines do. This is a continuing topic of interest, but one that cannot be addressed at present. For my initial thoughts on the matter see “Ted Chiang and what it is like to be an AI.” For why these arguments are category errors, see Dario Amodei’s “Urgency of Interpretability,” the implications of which for AI gaining something like “intentionality” should be obvious.