Some Art in San Francisco, Part 1

Mélanie Courtinat @ Gray Area; "Infinite Hope" @ Jenkins Johnson; Davey Whitcraft @ Themes + Projects, Test Strip Gallery @ CCA

Mélanie Courtinat at Gray Area

I wrote about Courtinat’s new video-game work at Gray Area for e-Flux Criticism. Read the full review here.

Infinite Hope at Jenkins Johnson

Those unfortunate few who have been pinned into conversations with me about art in the past two years know that I am bullish about photography and, more generally, about the state and status of the image. I have some writing on that to come, including in the form of thoughts on Peter Szendy’s new book For An Ecology of Images (Verso 2025), as well as a review of Second Nature: Photography in the Age of the Anthropocene, which originated at the Nasher Museum of Art and is now up at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford.

My refrain is that, after a decade of painting occupying the bulk of the political and commercial discourse, we are due for a resurgence of interest in advanced photo-based image making in digital and analog forms (and everything in between). Second Nature is an early entry in this resurgence, but so is MOCA LA’s exhibition about photorealism since 1968, a tentative step in the direction of reviving image discourse, but one that isn’t ready to give up on painting and its promise of resistance to the so-called “glut” of images circulating today.1 Of course, hanging over this entire interest, and animating its urgency, is artificial intelligence and how it is changing the stakes of image making, but we’ll have to put that to the side for the moment.

Infinite Hope was a welcome addition to what we might think of as the need to “reintroduce” audiences to photography. The show featured work by Gordon Parks, Kwame Braithwaite, Ming Smith and Rene Cox. On first glance, Cox’s work appears somewhat out of place in this mix, her’s being a practice engaged in staging and posing what are to my mind some of the strongest photographic images of the past 25 years, images that are intended as “Art” and thus bear comparison to all that the museums and galleries and biennials have to offer, whereas Smith and Braithwaite and Parks are perhaps better understood as photographers, even if Smith attempts to up the artistic ante of her works by embellishing her prints with paint.

A main thrust of Infinite Hope was a celebration of Black History during its titular month, and photography’s relationship to documentary is important in this effort. But in these photographs there is nearly an entire history of practice demarcated, from street photography and the “decisive moment” to studio portraiture, conceptual polemics, and celebrity snaps. That the show features Black history and identity in a major key is of course important, but so too is the minor key of form that risks being muted when what so many viewers will be attracted to is the works’ content.

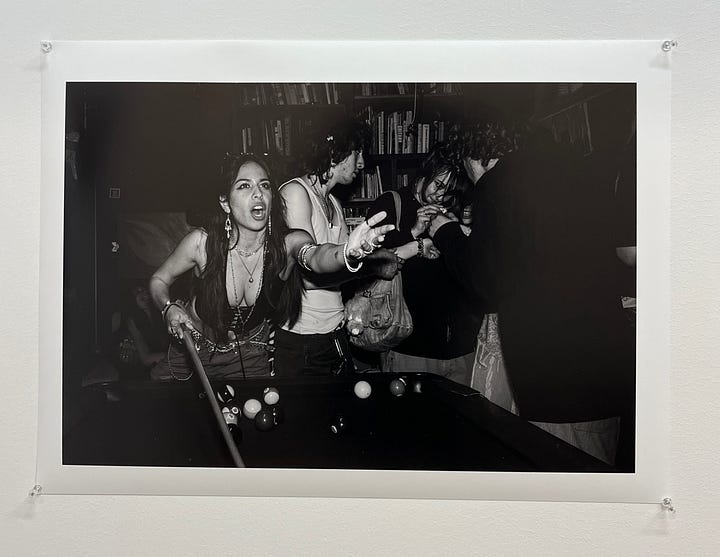

Hence why Cox’s inclusion in the exhibition seems particularly apt, because form is salient to Cox. And that salience carries over and makes it possible to see in images, such as Ming Smith’s picture of Grace Jones (see below), the work of self-conscious composition and high image intelligence — the geometry of the shot, the mirror, and the figures captured rivals the complexity of Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and anticipates by four years Jeff Wall’s A Picture for Women (1979), which has received more attention in the critical discourse.

The show is now closed, but I hope it’s a harbinger of more photography shows of similar quality to come.

Davey Whitcraft at Themes + Projects

I appreciate it when artists working with the moving image do more than simply set up a monitor to be watched. Framing and installation matters to the experience, in other words, and perhaps the best part of Davey Whitcraft’s show at Themes + Projects in the Minnesota Street Project galleria is the monitor setup of his work To Those Who Create The Future (2025). The four-square grid of gold-framed flatscreens is a great presentation. I particularly liked how the cords were caddied, though I would have preferred they be uniformly spaced from the right edge of all four monitors, but never-mind that.

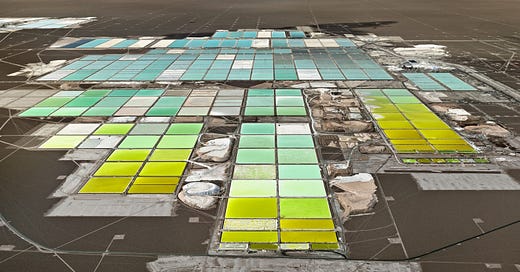

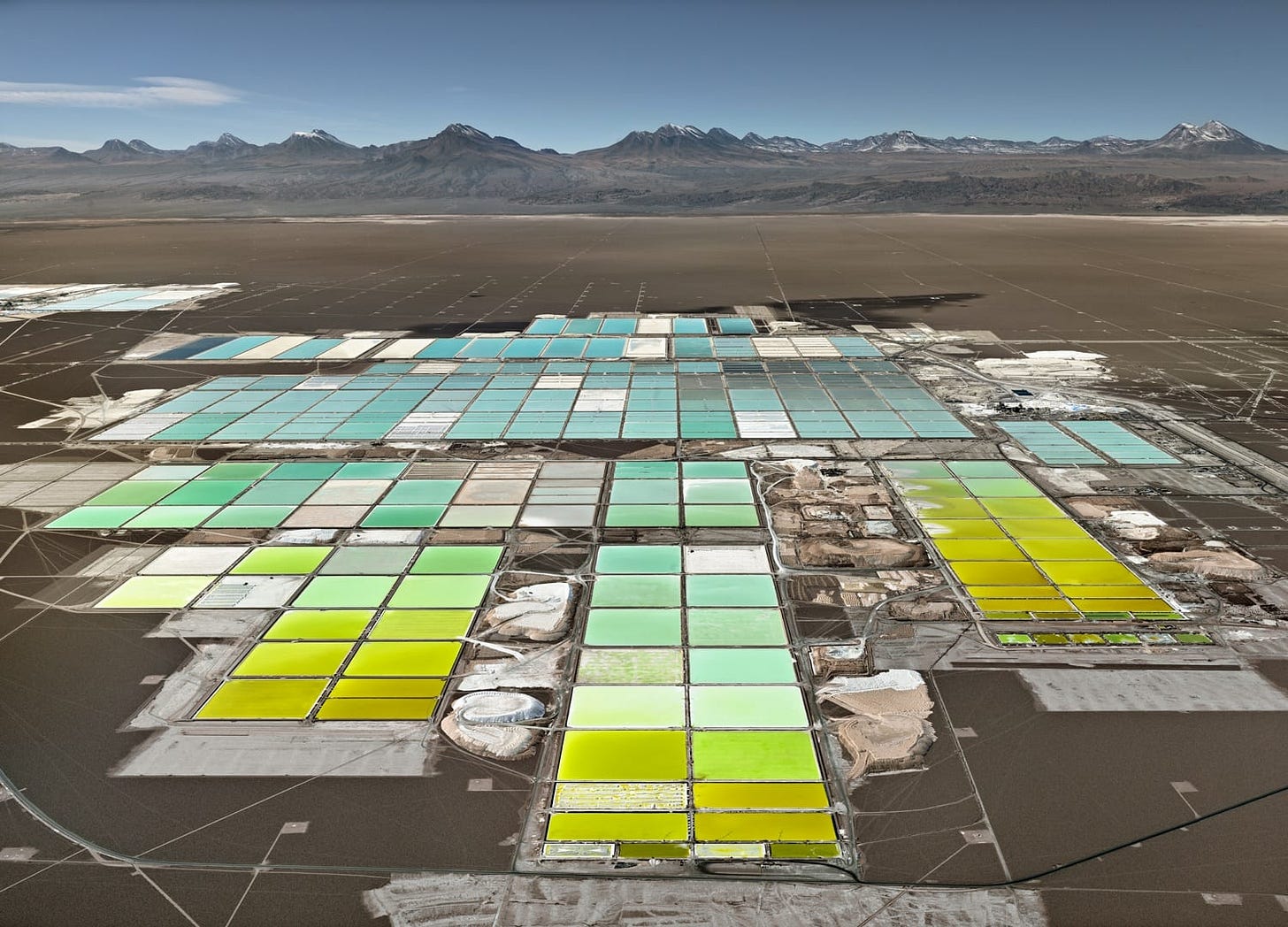

This may come off as glib, but the subject of To Those Who Create The Future is lithium (the key element in rechargeable battery technology), and one of the sites that Whitcraft captures in this otherwise pretty conventional film-poem, which somehow still owes a lot to what Stan Brakhage was doing in the 1950s, is the lithium mines of Chile’s Atacama Desert. The Atacama mines seem to be a compelling subject for environmentally-conscious photographers. Edward Burtynsky, probably the premiere aestheticist of the Anthropocene, chose it as a subject back in 2017.

And Burtynsky’s photograph reveals how the grid of Whitcraft’s work finds its direct analog (if not antecedent) in the geometries of the mine’s evaporation pools. To be fair, Whitcraft’s own documentary photographs of the mines reveal this as well. But beyond those documents, it’s not entirely clear to me how Whitcraft’s work here is “about” what he calls “the impact of lithium mining” and its role in “economies based on extraction, the ongoing impact of colonialism, the role of Silicon Valley, and the spread of politicized ideas online.” That’s asking a lot, both of the viewer and of the art.

Landscapes as dramatic as the Atacama are just rife with low-hanging aesthetic fruit. Add in the equally dramatic engineering feats of which humans are capable when the incentives are seemingly priceless, and the art almost makes itself. For example, a recent article in NPR about just this issue — lithium mining in the Atacama — featured photographs by Cristobal Olivares, all of which are good, but one of which matches (if not one-ups) Burtynsky’s. The juxtaposition of the almost abstract green pitch with the surrounding highest-of-high desert expanses is, in a word, stunning.

I think I am meant to think about this pitch with the same disgust I feel when occasionally from the window of an airplane I see golf courses carved out of equally unforgiving surrounds, such as Nevada or Baja California, but I can’t. The extremity of the gesture, the universality of the sport (of soccer, not golf), and the framing of the picture overcome, at least for me, the moral lesson such pictures are meant to teach. Outside the frame I’m willing to consider it an aesthetic feat that rivals almost anything that has been made under the heading of earthworks since the 1960s, but then I think about Burtynsky’s lithium mine in much the same way.

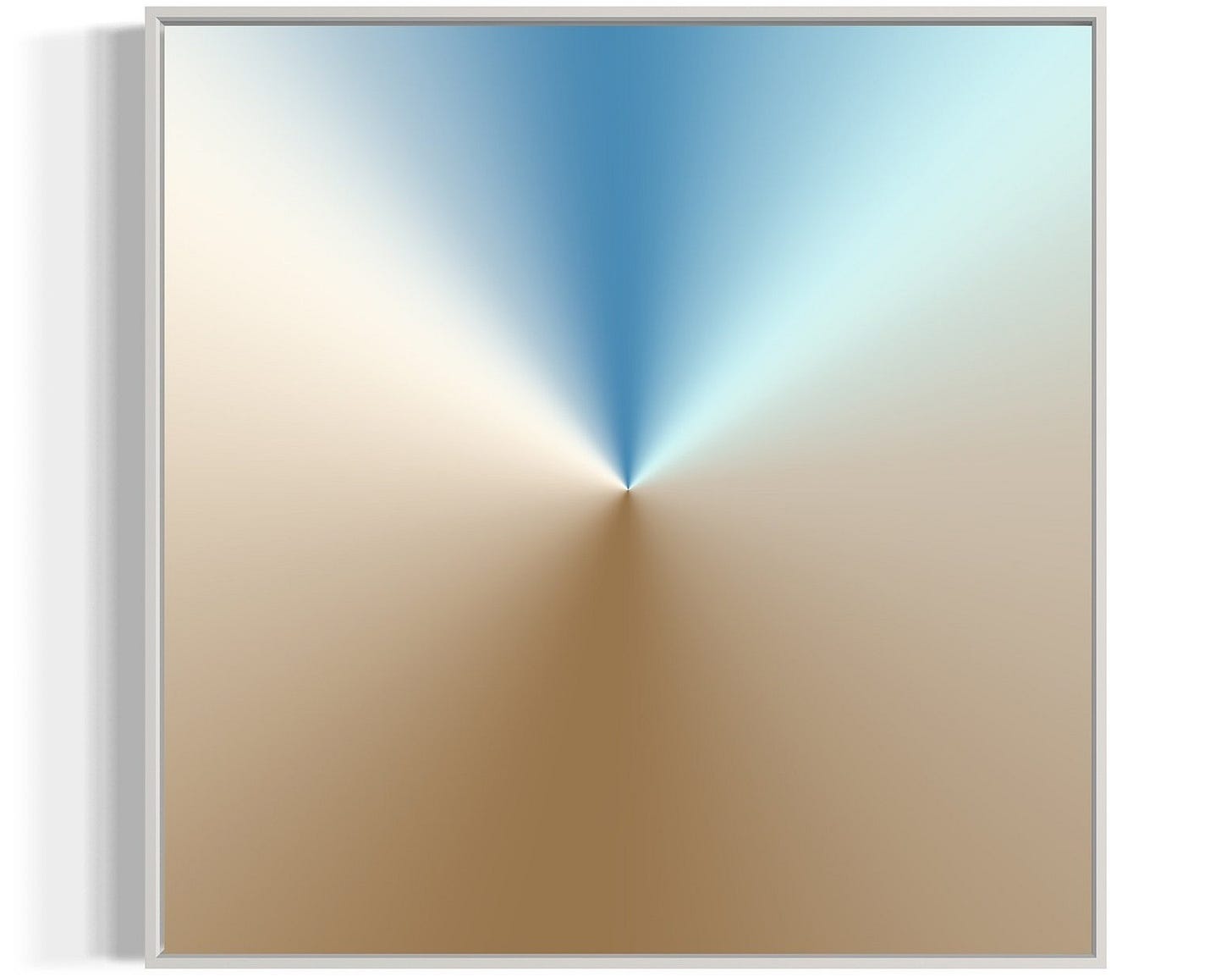

Perhaps Whitcraft is aware of the attraction that too direct a representation of such sites might hold. The other works on offer are images that digitally manipulate, or wholly reengineer, the documentary pictures to offer something more color-field and putatively abstract. One could go so far as to push the mining metaphor and say that what Whitcraft is doing is “mining” the image in some way that is parallel, or homologous, to the mining of the lithium that is pictured in his more documentary images, that in “extracting” color and shade to the exclusion of all other axes of differentiation — shape, form, line, etc. — the images perform in some sense the kind of violence that mining exhibits upon the land (and presumably the communities that make their lives on it). That would be my press copy at least.

My problem with it is that the “underlying asset” that is being mined here is just no longer recognizable or even legible. The process of “deriving” the image is mysterious (note: these terms in quotes are my own, not Whitcraft’s), the way that any modern industrial or technical process is. What matters then, in most cases for modern products of any sort — and yes, these images are products like any other — is the outcome. And for art, if the process of their derivation is important to recognizing the work as a work of art, then that process has to be recognizable in the work itself in some way. The politics that Whitcraft apparently wants represented in or by his work are erased by the fact that his images are so processed as to become untraceable to what made them. To say these pictures are about lithium mining in the Atacama and all of its attendant issues, from extractivism to colonialism, is what fails them as pictures, pretty though they may be.

That’s a question that’s worth considering, but one I’ll have to leave to the side for the moment: must pictures of the “rape” of the earth — as some would call it — look so appealing?

Anonymous at The Test Strip Gallery, California College of the Arts

I confess: there was a door propped open and I walked through it.

I’m a sucker for art and design studios, and on my first trip to the California College of the Arts (CCA) to see a show at the Wattis Institute (on which more below) I decided to seize the opportunity to walk around the studio spaces. In all of the detritus that accumulates over the course of a semester’s design studio, and lacking any and all context, there is often a lot of aesthetically interesting and just very cool stuff to see.

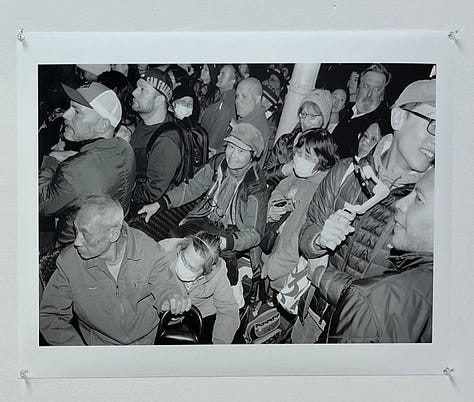

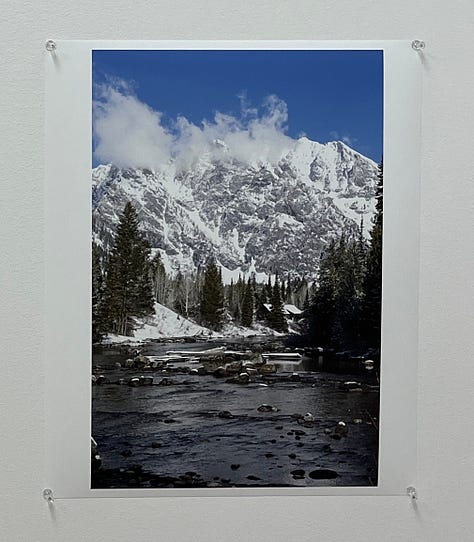

Along the hallway of one of the second floor studios at CCA is what’s called The Test Strip Gallery, essentially an alcove with space for “pinups” of the kind that happen often in these environments and in which feedback from peers and faculty is given. And what I saw installed there was a collection of images, the author or authors of which I can’t tell you, but about which I can say this: they were really good. All were modestly and variably sized (no large formats here); some black and white, others color; some landscapes, some documentary, some self-consciously ambiguous or “pictorial.” It was, to my eye and mind, a very strong showing.

I have no idea if these were the products of a photo studio or something else (and I’m not a reporter, so no, I did not go chasing down students or staff to ask all the requisite questions about it; I prefer the mystery and artifactuality), but if this is what’s going on at CCA, then I’m here for it.

This resistance is commonly thought to stem from painting’s capacity to “slow” the image either because it is more “material” (both literally and figuratively) than natively photographic or digital images, or because it is more processual or procedural (i.e. it takes time to make). One might have been able to take this seriously around 2000, but by 2025, in the face of painting’s total capitulation to, and dependence on, its mediation via digital imaging, any arguments for painting as some speed bump or limit to the circulation of images is evidence of nostalgia at best or ignorant delusion at worst.