On "STEADY" at The Wattis Institute; or, Some Art in San Francisco, Part 2

Thoughts on sculpture in general and work by Michelle Lopez and Ester Partegàs, with an aside on Vincent Fecteau (the Alex Honnold of sculpture? - maybe).

Steady at The Wattis Institute, CCA

A quick aside on sculpture

Let’s get this out of the way up front: sculpture is hard. It’s hard from a market standpoint; it’s hard from an aesthetic standpoint; and it’s hard from a discursive standpoint.

After what one might call the “relational” and “social” turns in art of the 1990s and 2000s, today it is the case that much sculpture appears as artifacts that speak either to an alternative present or a reimagined past (rarely a hoped-for future) when they aren’t speaking directly to representations of the human or humanoid body. Some sculpture, of course, just speaks to itself.

The critical orientation of much of this work is towards the codification of some claim to a “way of being” in the world, both broadly construed (as in the many works one encounters that implicate, say, “labor,” wherever and however it appears) and narrowly (as with works that want to pinpoint the ethical dimension of some specific way of being that isn’t majoritarian). In every case works are assumed to be suffused with social meaning from the jump, whereas it once was sculpture’s project to secure that meaning through its presence and effects.

From an aesthetic standpoint, sculpture continues to be challenged by its proximity to the literal, that it simply is its materials and processes and scale of address, and whatever metaphors its forms and effects might conjure are fleeting at best and overdetermined at worst. From a market standpoint, fabrication, shipping, handling, and storage are just geometrically more expensive than they are for so-called “flat” work. Sculpture takes up real estate, and there’s a real cost to that.

All of which is to say artists who make sculpture are already working against serious headwinds, and deserve encouragement for it. It also means we need to do the most we can to improve and advance the discourse of sculpture, because the aesthetic challenges are up to the artist (and might find ways of being redefined if the discourse improves), and the market challenges will remain what they are until or unless the prices of energy, material and real estate undergo some massive downward revaluation, which seems unlikely.

On Michelle Lopez

So what to make of STEADY at The Wattis, a two-person show of recent sculptural works by artists Michelle Lopez and Ester Partegàs? Let’s begin with Lopez, who I think presents a stronger set of works, though ones that aren’t best served by the discourse that has been marshaled to describe what they’re purportedly about.

For the past few years, Lopez has been working with steel cable, “wire rope” in the industrial language, creating in some cases simple, in other cases complex, arrangements of the material, and often “flocking” it with monochrome nylon fibers that give the cables a colorful and apparently soft coating. The cables are bent in roughly ninety-degree angles, sometimes combined into full square shapes, and exhibited alone, in pairs, and sometimes in aggregates that appear to lean against each other, or in stacks.

The works come across as at once obdurate and shaky. If you have ever handled cables of these diameters you’ll be aware of just how little like “rope” they behave. This stuff is unruly.

Braided steel cable is designed for tension, not compression, and Lopez has found, or at least presents, a sweet spot where the material’s properties offer up an edgy equilibrium, or at least its appearance, as the arrangements get a bit of an assist here and there from a well-placed tack-weld or floor anchor. The “single line” works might be the most successful, insofar as you will inevitably ask “How is it that this thing is standing upright?” and the subtle mystery there will likely hold your attention.

Lopez edges here in the direction of the best works by someone like Tara Donovan, who has made a career of seeking out often banal mass-produced materials and aggregating them in novel and surprising ways. The industrial rawness of Lopez’s ropes means that such obsessive and patterned aggregation is unnecessary, and would be besides the point, but the work is sustained by the fact that those materials are presented as more than mere “readymades,” and that “moreness” resides in their flocking (when it’s there) and their uprightness, in which Lopez seems to find singular interest.

As demonstrated by the earliest of Lopez’s works included in the show: each titled THRONE, and created almost a decade ago, the two roughly-seven-foot tall constructions exhibit a handmadeness and arbitrariness-of-composition that Lopez has since left behind (at least in the rope works).

What seems important in these pieces is that they are indeed standing, and as much as they might stand over us, they don’t exactly stand up to us or against us. These works are “weak” in the sense that one feels the need to be careful around them, for fear of knocking them over, whereas with the rope works, yes, one might feel the need to be careful again, but here it is more because there’s no telling if and how those things might fall and, if you get too close, whether you escape with a snag in your pants or a trip to urgent care.

The question we have to ask is this: is such a concern with weakness the animating force of these things? Provided it’s an intended effect (and according to Lopez and her advocates it is), does weakness, or really more one’s assumed or induced anxiety over it, constitute a worthwhile or relevant aesthetic category of experience?

Perhaps. There is an argument to be made that “weak sculpture” could be an analog to something like Hito Steyerl’s idea of the “poor image.” That argument would no doubt hinge on the concept of “precarity” as an existential and political condition, which the sculptures would then reflect or figure. It would also fit well with current accounts of Lopez’s work that see in it #resistance to all sorts of bad ways of being, such as investments in “closed systems,” “patriarchal power,” and “absolutes” of one kind or another. In “weakness” then one could presumably find openness and contingency, other kinds of “power” and better ways of being. One could even see building a genealogy of “weak” work, which might include artists such as Gedi Sibony, pass through a certain strain of post-minimalism (Barry La Va, Eva Hesse), and link up to Jean Tinguely (though I don’t sense that this is the family tree Lopez either imagines or wants).

As I say, “perhaps”. Weakness as aesthetic experience, as leading towards other ways of being and a different kind of power, has a very distinct Christian valence to it. That’s not in and of itself a problem, but I suspect it’s not the theoretical armature that is thought to support the otherwise explicitly feminist claims that STEADY seeks to make.

An aside on Vincent Fecteau

On the occasion of STEADY the Wattis invited Michelle Lopez and Vincent Fecteau to engage in an artist-to-artist conversation, which proved both frustrating and illuminating. Artists are sometimes very good at getting out of one another insights into each others’ work and process and precedents that curators or critics or other interlocutors are just not acute enough or dialed-in enough to get at. But for that to happen, it’s best if one artist is the inquirer and the other the subject of inquiry. When, as happened in this conversation between Lopez and Fecteau, the artists were assumed to be playing both roles, the results could be quite weak (and not in the productive way described above).

What helped the conversation along structurally was that Fecteau and Lopez are just such very different kinds of sculptors. The extreme contrast between their work and interests really does help bring to light what kind of project sculpture is at present and in which these artists are arguably engaged.

At one point during the Q&A Fecteau said something to the effect that he is making the same sculpture over and over, which is prima facia absurd when thinking about how he is probably the premier artist of unrepeatable irregular geometries, how the spaces and shapes and surfaces his works manifest would be nearly impossible to model in any kind of computational space, that all traces of materiality for its own sake are absent, and most traces of the artist’s or any other “industry” is subsumed within the composition of the whole, which is more emergent than constructivist — and how it’s exactly this quality, their resolutely unique human-madeness (as distinct from mere “handmadeness”) that most likely accounts for their popularity, if not their import, today as acts of underdetermined human creation in an overdetermined and post-human world.

That’s one way of putting it, and it wouldn’t be Fecteau’s necessarily, because on his own admission he doesn’t really “know” what he’s trying to get at, what sculpture he’s trying to make. Everyday he comes to the studio and simply responds to whatever work is underway as it exists at that moment. There is no other context. No outside. Whatever problem is trying to be solved, whatever sculpture is trying to be made, it is internal to the process of Fecteau’s own mind and body, his own psyche. It may be a misnomer even to call it a “problem,” as this is the state — the state of making — that Fecteau claims is the one in which he is happiest or most satisfied. That he has been able to organize his life so as to be able to spend vast quantities of time alone in the studio with his work is by his own admission something of an achievement, not because it satisfies some project of what it is to be an “artist” — unalienated labor and all that — but because it satisfies whatever it might be to be Vincent Fecteau.1

Which is why, ultimately, one could choose to understand Fecteau’s work in some very real sense as therapeutic. Like much sculpture, like much art, its project is about a way of being in the world, but in this case the way of being is so radically particularized, so centripetal, so utterly monadic that it negates any claim to a “way” of being that might be recognized or understood as one from outside. I would submit that the one person with the best view to Fecteau’s work and what it is about, not in the sense of what it means, but what project it serves, is his therapist.

This is not to dismiss Fecteau’s practice, but to uphold it — and it would be a mistake to submit to the language of psychoanalysis here and imagine that there is some empty center, some impossible object of desire, which stalks and structures Fecteau’s fantasies and so informs the compulsions of his work and practice; there may be that, but I don’t see it in the work.

What I see, to a certain extent, is the rock climber Alex Honnold free soloing the face of El Capitan. Not the feat itself, the spectacle of it, or the “lifelong dream” of conquering some part of one’s self by doing something that would be both mind-and-body shattering for every other human alive or who has ever lived (which is why you make a movie about it) — no, just the doing of the thing: an activity that entails the absolute unburdening of the mind. No history. No politics. No other or “others” of any kind. No before or after. Just a practiced and measured doing of this certain thing, in its own moment, which these artists know how to do differently than anyone else. That’s not climbing rocks (for Honnold) or making sculptures (for Fecteau), but doing something — a doing — that is free of all disturbance, and yet remains a matter of life and death.

On Ester Partegàs

That was a bit much. But it helps us understand why Fecteau’s work couldn’t be more different from Lopez’s work. Lopez’s sculptural practice is all about disturbance, of mind, of body, of social fabrics, of identities, and it wants to picture or feature those disturbances through its resistance to them. It is work that is at every moment mindful of the external conditions that pertain, from the space in which the works themselves will be situated or installed, to the histories of art and sculpture that inform her interest in the ideologies of their aesthetics, to the limits of her own embodiment, actions and capacities. There may be more immediate and apparent danger in Lopez’s work (to the work, to the bodies that fabricate it and install it), but that is part of its aesthetic, and is meant as a sign of its disturbances. Those may be real — the heft of the metal, the pull of gravity, the capacity for collapse — but they’re also metaphorical.

Partegàs’s work is more muddied in its pursuit of these kinds of instabilities. Her inclusion of commercially fabricated objects — disco ball, polyurethane chair, dish sponges and scourers, in combination with FastMaché (basically paper maché) forms of ambiguous lineage (oversized laundry baskets according to the title) — creates curiosities at best. The instabilities invoked are neither structural nor procedural but superficial — i.e. those instabilities (they don’t feel like disturbances) come from the worn surrealist strategy of the odd juxtaposition, with Partegàs’s FastMaché perhaps acting as a kind of real-world manifestation of the interpolations and creepy figurative infills that one sees in AI-generated images today.

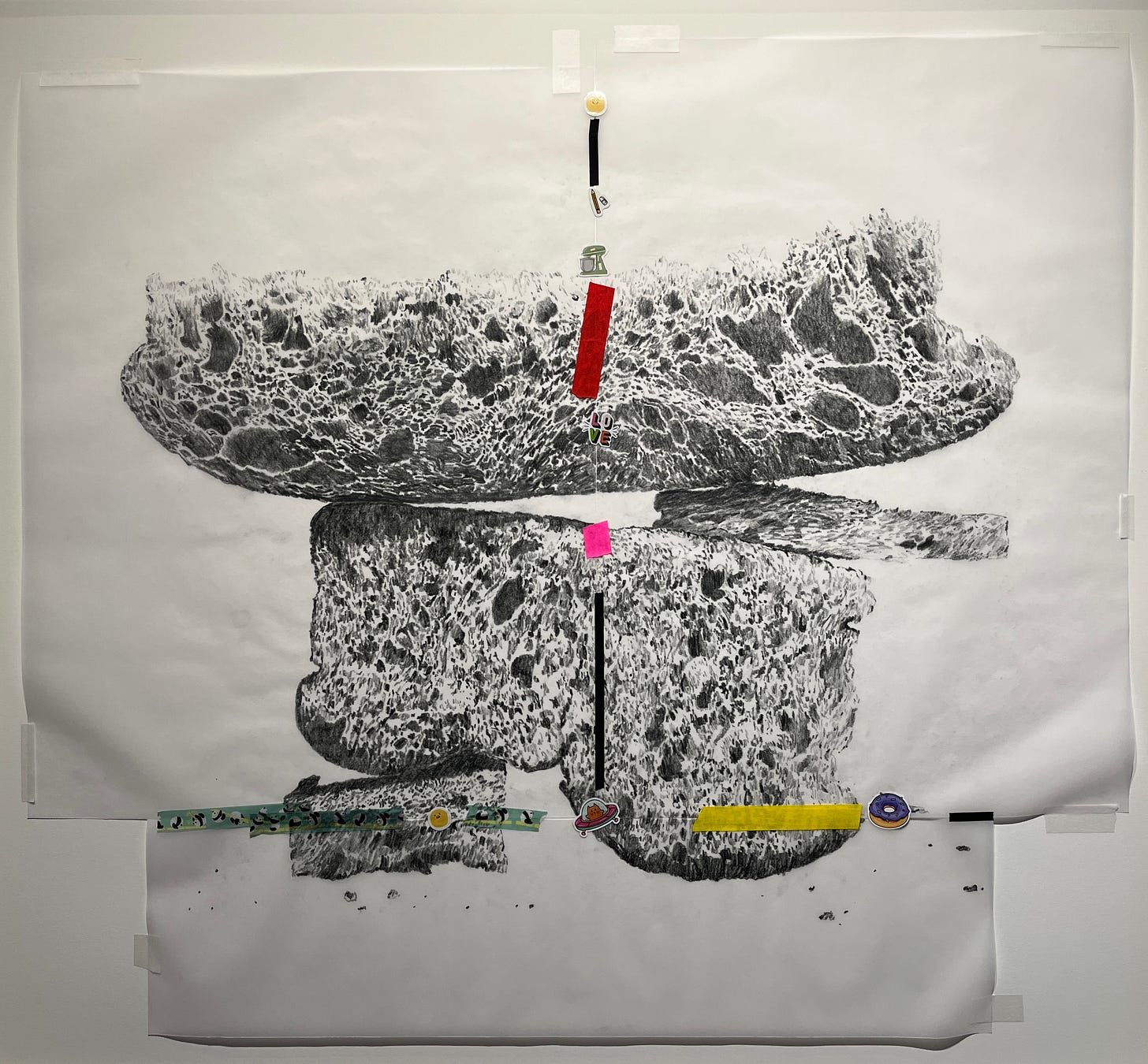

That Partegàs is stuck at the level of the image can best be seen in her drawings of bread, which may be the strongest works presented in STEADY. These graphite on vellum works are, on first glance, genuinely ambiguous. Partegàs’s fidelity to the image does not make them more legible as pieces of bread but actually less — on first glance I could not tell if what I was looking at were slices of sandstone or coral or some other porous mineral deposits. Even the “stacking” of the hunks and slices didn’t read that way until I took a picture of the work, which reduced the incident of the seams between the sheets of vellum and minimized the children’s stickers and highlighter tape that tacks them together. In this case, those “found” elements, analogous to the disco ball and sponges in the sculptural work, serve to heighten the perceptual experience (by disturbing it) rather than confusing it (again, sculpture is hard!).

Partegàs’s work points in the end to the difficulty that sculpture confronts when it attempts to moderate its aesthetic options by working in a space that belongs to images and legible objects rather than in the space that belongs to form. Readymade objects ultimately come with off-the-shelf meanings, of both the obvious and the academic kind. And if the work is going to deal with that condition, of sculpture’s mechanisms of signficiation in a world dominated by the image, well then it would be Rachel Harrison’s sculpture, with Partegàs’s drawings coming in a close second — but then of course we would be dealing with drawing, and that’s another topic.

As I write this I realize it may be objected that I am just describing a whole range of idiosyncratic but unqiue practices, sculptural or otherwise. The artist that comes to mind is Bruce Nauman — unique, influential practice, and Nauman’s psyche is the door through which most critics and historians want to step in order to get a better handle on his work, and for good reason. But as much as Nauman’s “mind” is the subject as well as object of his art, it is because the art is self-conscious about it (those quotation marks matter). Nauman’s work can be read as channeling raw anxieties and compulsions as these are determined and shaped by social and cultural surrounds. Nauman’s “self” is always constructed, mediated, represented; and it is those constructions and mediations and representations, their means and mechanisms, that are at the heart of his art and what it is about. And I think this is the same for many artists who appear “enigmatic” and as creatures of the studio but who are really very cognizant of their connectedness to the outside world. Fecteau, I believe, would be fine were the outside world to disappear.

This is so interesting, considering our debate yesterday. I love the works here that you panned and relate to them completely.

Ester Partegàs's "Two Moons" is immediately evocative, conjuring up the delicacies of home life, the fantasies of nightlife, and the brokenness of all of those intimacies in our current life now.

I don't have as fast of a read on "knead, penetrate, let go (cat spaceship donut)" but I liked it as well: the textures of the pummous stone (?), the strange office tape, the tiny stickers. This combination is satisfying, even if it doesn't communicate a single clear story as fast.

I appreciate you saying you're comparing these works to Bruce Nauman’s, "whose “self” is always constructed"...And also I think this reveals an important point about how art standards consider masculinity / public life is a worthy subject where as feminitiy and the domestic are still thought of as throw aways and unworthy of deep analysis - ESPECIALLY when they have references to mothering and children.