Image Intelligence; or, Some Art in San Francisco Part 4

Sophie Calle @ Fraenkel; Catherine Wagner @ Jessica Silverman

On Sophie Calle

When I first saw Sophie Calle’s Take Care of Yourself (2007) installed in the French Pavilion at the Venice Biennial I thought it was too much. Not the idea of the work, Calle’s solicitation of over 100 responses from other women to a breakup email Calle received from a (former) lover, but the presentation itself, which overwhelmed with text and image, perhaps by design. Though I wasn’t thinking of it in these terms at the time, the installation induced in its viewers (at least in this viewer) an experience of scanning and browsing that modeled how one often experiences information retrieval and consumption online.1 One could spend a few hours reading and watching all of the entries expressing solidarity and sympathy of one kind or another, or one could get the gist, move on, and wait to page through the inevitable accompanying publication if truly enamored of the conceit.

Other of Calle’s projects have a similar tendency to overwhelm, if only because they overwhelm the artist too. Since perhaps her early and most notorious work The Address Book (1983) — in which Calle found a lost address book and proceeded to contact all of the owner’s friends and acquaintances in order to “paint” a picture of him, the results of which she published over the course of a month in the Parisian newspaper Libération, to the chagrin of the address book’s owner as well as the newspaper’s journalists; it’s the one project for which she has admitted to going “too far” — Calle has made a career of mining her own and others’ intimacies through behavioral commitments — inviting strangers to sleep in her bed; following someone around Paris for a number of weeks — that are both logistically and emotionally taxing.

After spending some time with these kinds of projects, though, you might find yourself asking: Doesn’t Calle ever get tired of this shit? And the answer, both merciful and endearing, is: Yes, yes she does.

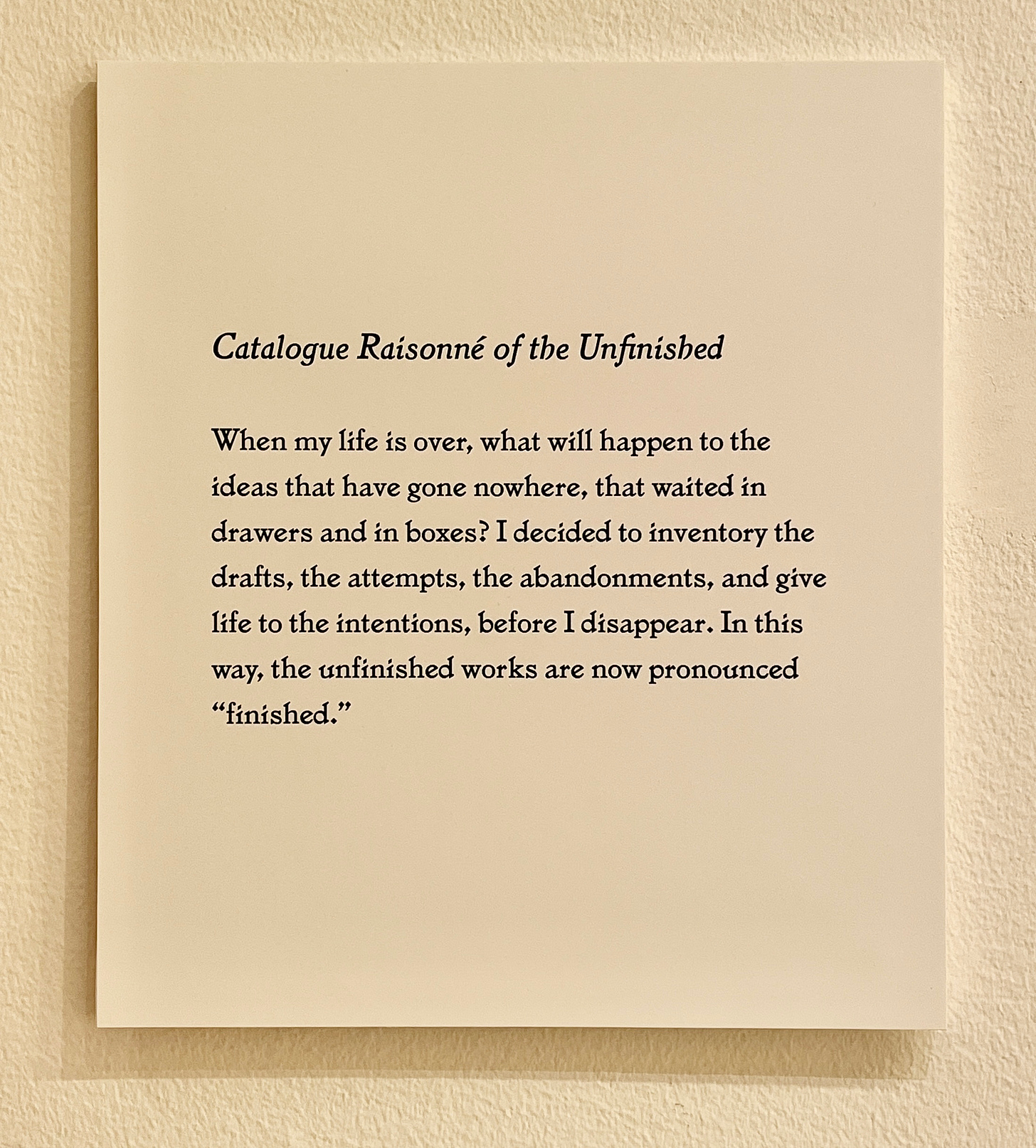

Calle’s presentation at Fraenkel Gallery is what she calls a “Catalogue Raisonné of the Unfinished,” which she describes as follows:

When my life is over, what will happen to the ideas that have gone nowhere, that waited in drawers and in boxes? I decided to inventory the drafts, the attempts, the abandonments, and give life to the intentions, before I disappear. In this way, the unfinished works are now pronounced “finished.”

And what she presents are a series of self-contained text-and-image works that detail how some of those budding behavioral commitments got nipped.

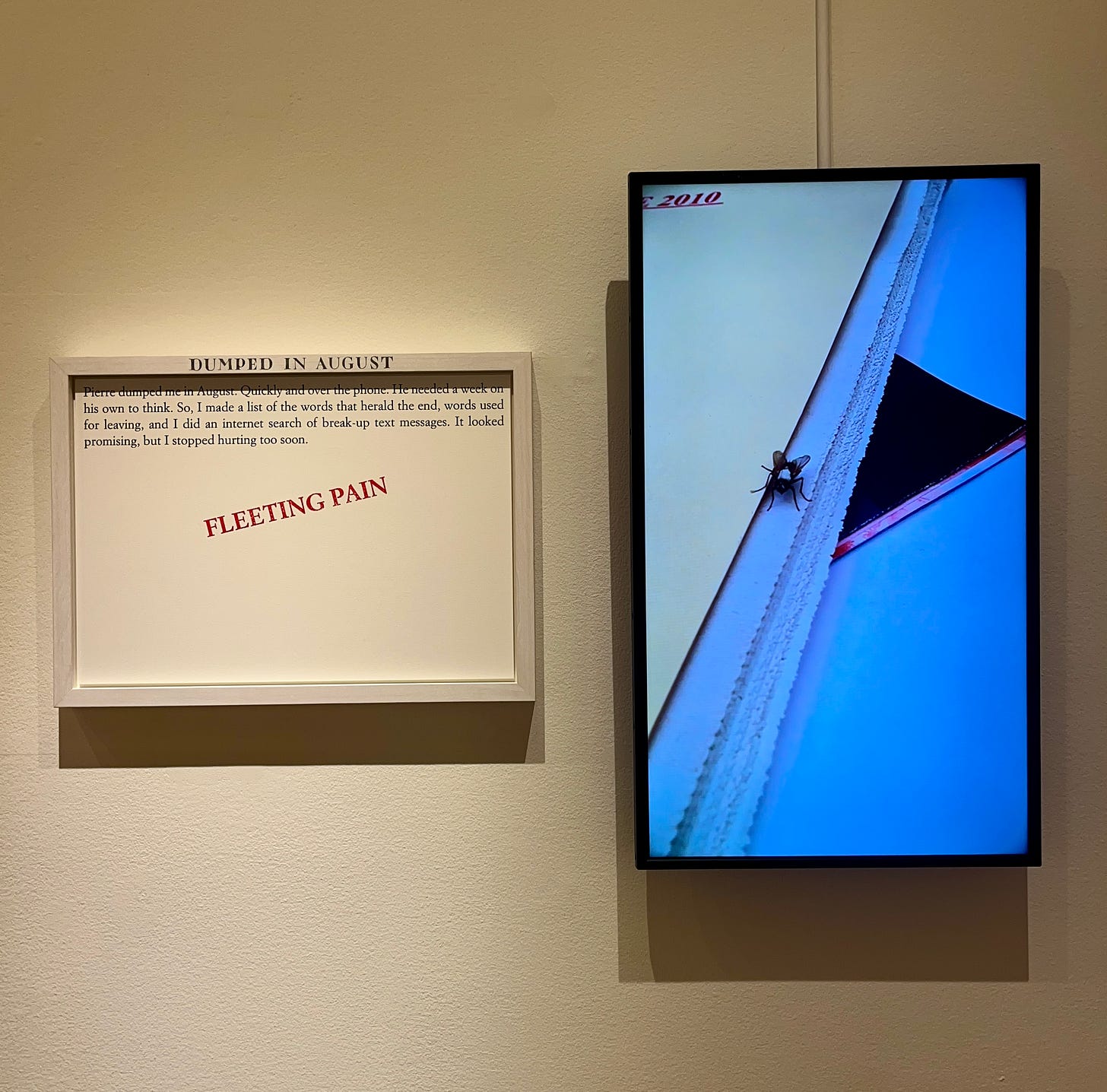

What sets Calle apart, even from artists who could be said to share in, or whose work stems from, her acute meta-psychological inquisitions (I’m thinking here of artists such as Leigh Ledare and Jill Magid), is that she is a masterful, aphoristic writer. Consider Dumped in August (Fleeting Pain) (2025), in which Calle explains in the text print:

Pierre dumped me in August. Quickly and over the phone. He needed a week on his own to think. So, I made a list of the words that herald the end, words used for leaving, and I did an internet search of break-up text messages. It looked promising, but I stopped hurting too soon.

Below which is stamped in red ink, as if by some bureaucratic functionary of the heart: “FLEETING PAIN.”

“…I stopped hurting too soon.” This made me chuckle. Poor Pierre. Sophie just wasn’t that into you. But seriously, it’s a testament to the enduring idiocy of the male ego that any fellow would get into a relationship with Calle, especially after 2007, let alone 1983. But Calle’s willingness to share, and the low-level eroticism that pervades her type of tell-all work, is catnip for mimetic desire. Men will fall for it, and obviously do.

It’s not all breakups; there are boredoms, and there are deaths. In Now What to Do? (Not Exhilarating) (2025), Calle explains how she solicited ideas for projects from visitors to a trio of her exhibitions, and that of 1,369 submissions she found none interesting enough to pursue. In the accompanying photographs, there is Calle, dutifully sitting across from willing participants, presumably listening to their less-than-exhilarating ideas, the transcriptions of which sit stacked below in a small vitrine, like an archive of disinterest.

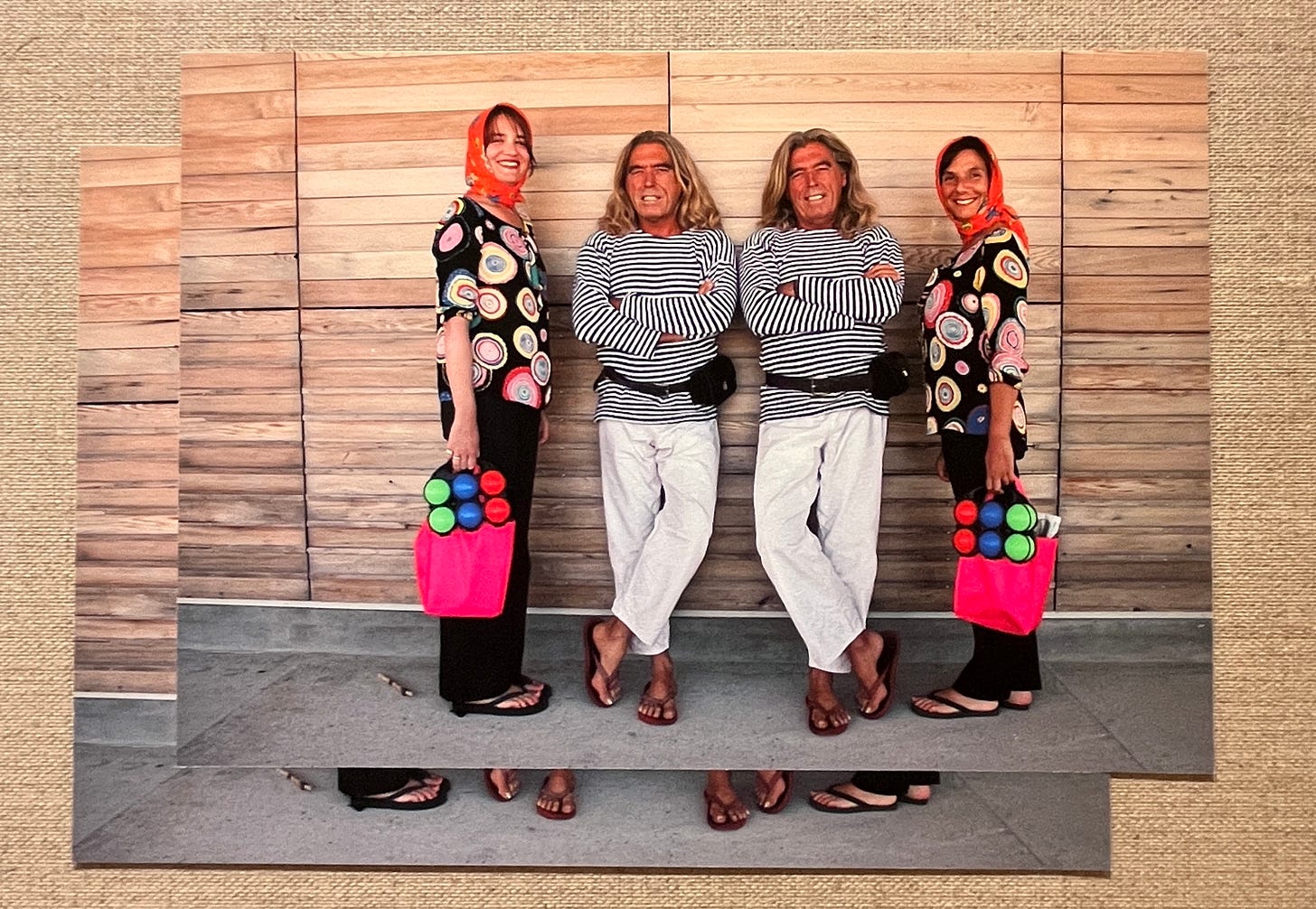

In Twins (Max Died) (2024), we see Calle and her friend “Cathy” posing in matching outfits with twins Emmanuel and Max Berque while on various vacations together in the Landes region of France (just south of Bordeaux). On the evidence of the photographs, these trips occurred over a number of years. The outfits and poses range from the mundane and youthful (there the four of them are sitting on a couch) to the theatrical and aged (with matching bicycles, motorbikes, and gas cans). My absolute favorite of these snaps shows Emmanuel and Max sporting long blond locks, stripped shirts and fanny packs — I just can’t imagine anything more French — flanked by Sophie and Cathy in orange headscarves and carrying matching bocce sets and magenta bags.

Of these trips and photo sessions Calle writes that “It was an enduring ritual in search of some culmination. But then Max died. Game over.”

That “game over” might come across as flippant, but Calle’s work is often conceived in terms of games with various types of rules, and one could read the words here as compensating in part for what could only be a real loss. It’s the great achievement of this work to make that loss felt by the viewer as well. The economy of image and text, the care that is evident in the photographs — for how the players look and how they feel about each other; there is real enduring enjoyment to this ritual — and the care that is given to their presentation — every photograph is doubled, with one print partially occluding the other, speaking again of loss — all combines to make one feel actual sadness. Not necessarily because one wants to see more of these pictures — the ones Calle gives us are probably enough — but because one wants the ritual to endure for the sakes of its participants and their bonds, however strong or even weak those may be.

The capacity for these works to generate narrative with the most modest of means, but with the highest of attention to form, is indicative of their, of Calle’s, image intelligence. It would be foolish to reduce her work to narrative alone, to make it about just what it says, because the work is always and at every point insistent on its form, on its status as a construct — a construct of images and texts as objects in the world (printed and collected, collaged and screened), always in deft combinations so as to produce something like “sincerity” when truth is impossible to pin down.2

Calle has long been a player of textual games and image games, and critics have learned to be wary. But these “unfinished” works speak to games gone awry, or left off, and it’s only the most paranoid critic, with his photocopies and push pins and strings of connections, who will see in these works, as in all of Calle’s work, the grand conspiracy of “Sophie Calle” — her proxies, her doubles, her monomanias — staged to suck us in and cheat us of our own sincerities.

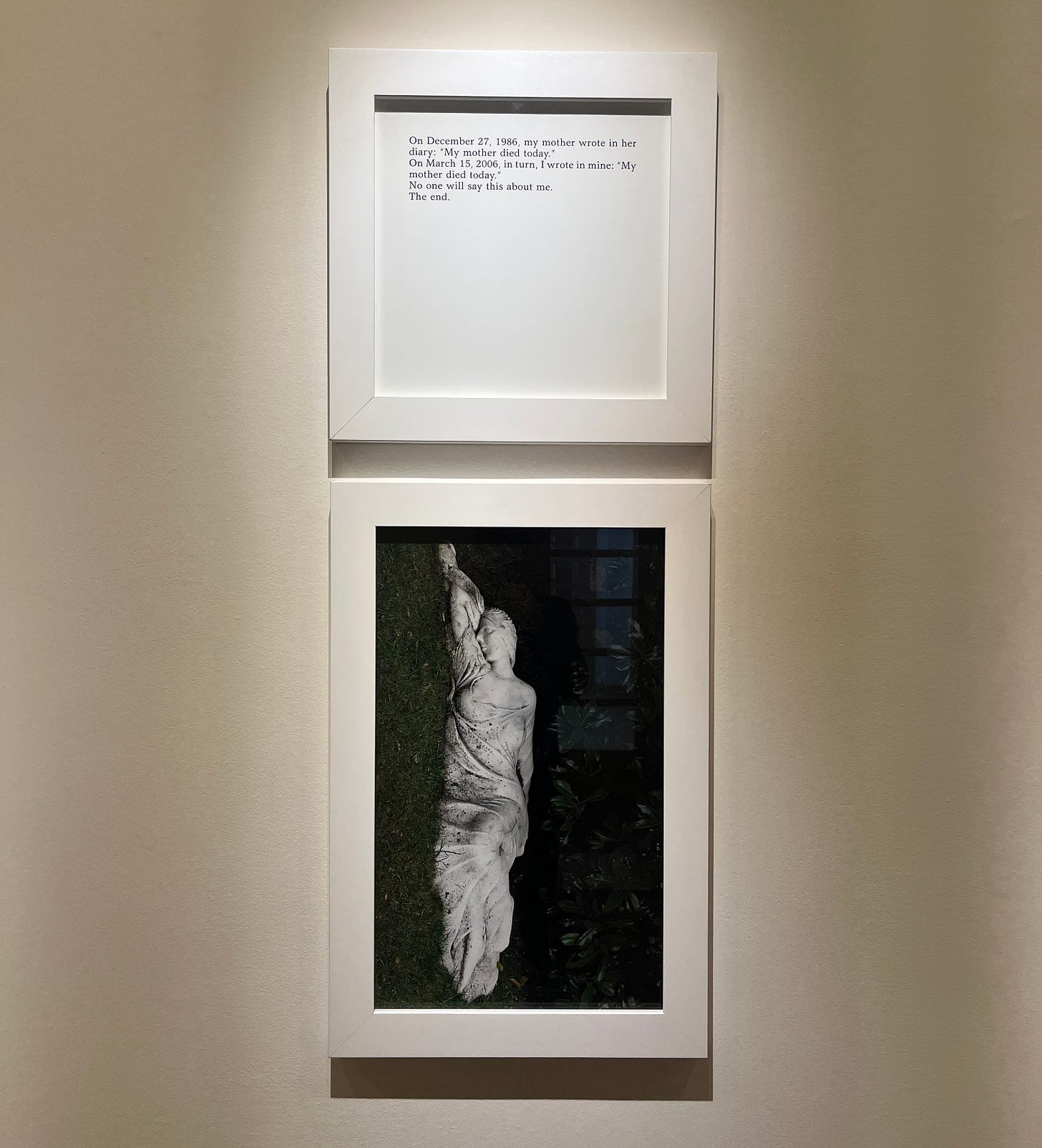

I don’t see that here. In particular, the game player isn’t there in the “Autobiographies,” the collection of works that deal with family history and the deaths of her parents. Consider Autobiographies (My Mother Died) (2013):

On December 27, 1986, my mother wrote in her diary: “My mother died today.” On March 15, 2006, in turn, I wrote in mine: “My mother died today.” No one will write this about me. The end.

I felt that as a punch in the gut. The accompanying photograph, a stone figure of a woman in repose, possibly funerary, is hung in portrait orientation as opposed to landscape, invoking an ambivalence in the image — she is both earthbound and ascendent — that is equally immanent to the text — is Calle expressing regret or resolve? One can’t say.

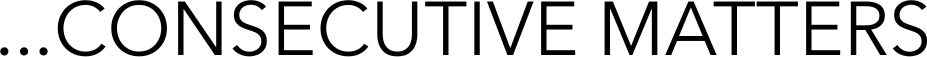

In Autobiographies (Morning) (2016), Calle accompanies a small photograph of herself (we presume it’s her) standing behind a headstone that reads “FATHER” with a large panel of text detailing her attempt to capture her father’s last word. The death of one’s parents is no laughing matter, and yet it is; it can only be. In the middle of the short litany about her father’s last week, Calle writes:

Wednesday: with a movement of his lips and eyes, / he asked for a kiss. / My father who never kissed me, wanted a kiss. / Could this very uncharacteristic gesture be his last word? / Thursday: Toilets. / Not a great word. He would be alive tomorrow for sure.

If you don’t smile at this you are dead inside and there is no hope for you. Humor and death go together; only the conspiracist can’t laugh. Calle finishes the text with:

He died on Monday April 6, 2015, at 6:50 am. / My father was ninety-four years old. / Not long before, when I asked him how he was doing, he responded: / “I’m not making any progress.”

I recognize this humor. The dying can be and often are funny about their own deaths. Apparently Calle’s mother was as well, choosing for the epitaph on her headstone “Je m’ennuie déja” (“I’m already bored”).3

Boredom. It’s an idea that gets strikingly little play in the writing on Calle’s work, which itself is far from boring. In fact, it seems to be designed to run away from boredom, to construct life as a game, in which sex and death and the nitty gritty of human relations, the things about which we are least inclined to talk about on a daily basis, are forced front and center, are made the stuff of Calle’s every day.

When my own parents chose to end their lives, the period between their decision and their action became filled with conversations — between me and them, between me and my own family, between me and my friends and my parents’ friends — that took on a depth and thoughtfulness that made much of whatever we had spoken of before seem superficial, seem weak. Here was my own family talking to me about the childhood roots of their own fears of abandonment, of lost innocence, of uncertain futures. Here were friends talking to me about their own parents’ deaths, about scenes of regret and pain. But here also were people talking about love and friendship and bravery.

One gets the sense that, like her mother, Calle may have been “already bored” with much that life was offering, had to offer, and so she made life itself into something like a game of chasing affects of one intensity or another, sometimes by turning the mundane itself into its own intensity. In response to one critic’s otherwise boringly perfunctory interview questions, Calle apparently shot back:

When did you last die? What gets you out of bed in the morning? What became of your childhood dreams? What sets you apart from everyone else? What is missing from your life? Do you think that everyone can be an artist? Where do you come from? Do you find your lot an enviable one? What have you given up? What do you do with your money? What household task gives you the most trouble? What are your favourite pleasures? What would you like to receive for your birthday? Cite three living artists whom you detest. What do you stick up for? What are you capable of refusing? What is the most fragile part of your body? What has love made you capable of doing? What do other people reproach you for? What does art do for you? Write your epitaph. In what form would you like to return?4

All good questions to take us away from the idle chitchat of the everyday. But take note of the first question and the last. Death can be funny, but it’s never boring.

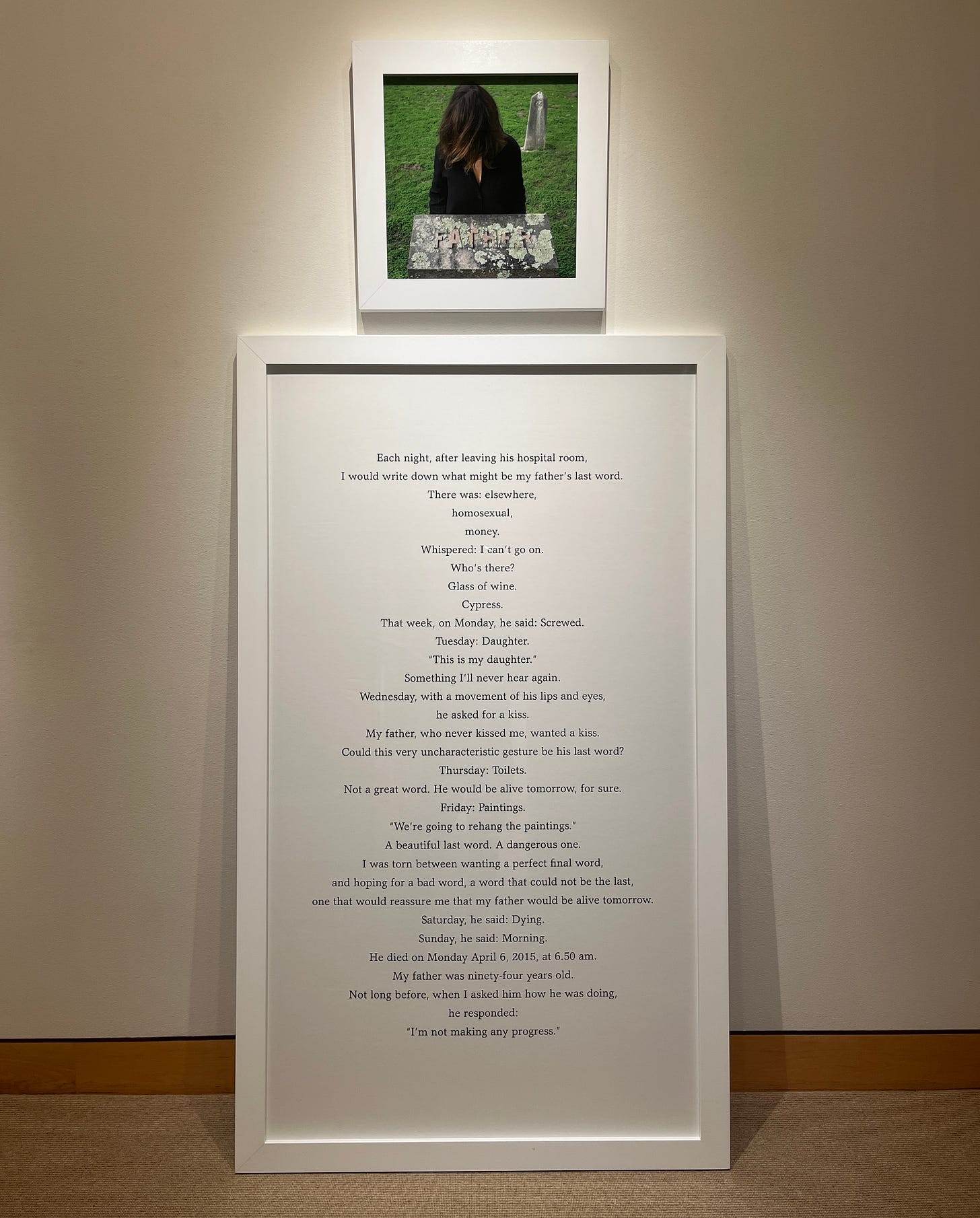

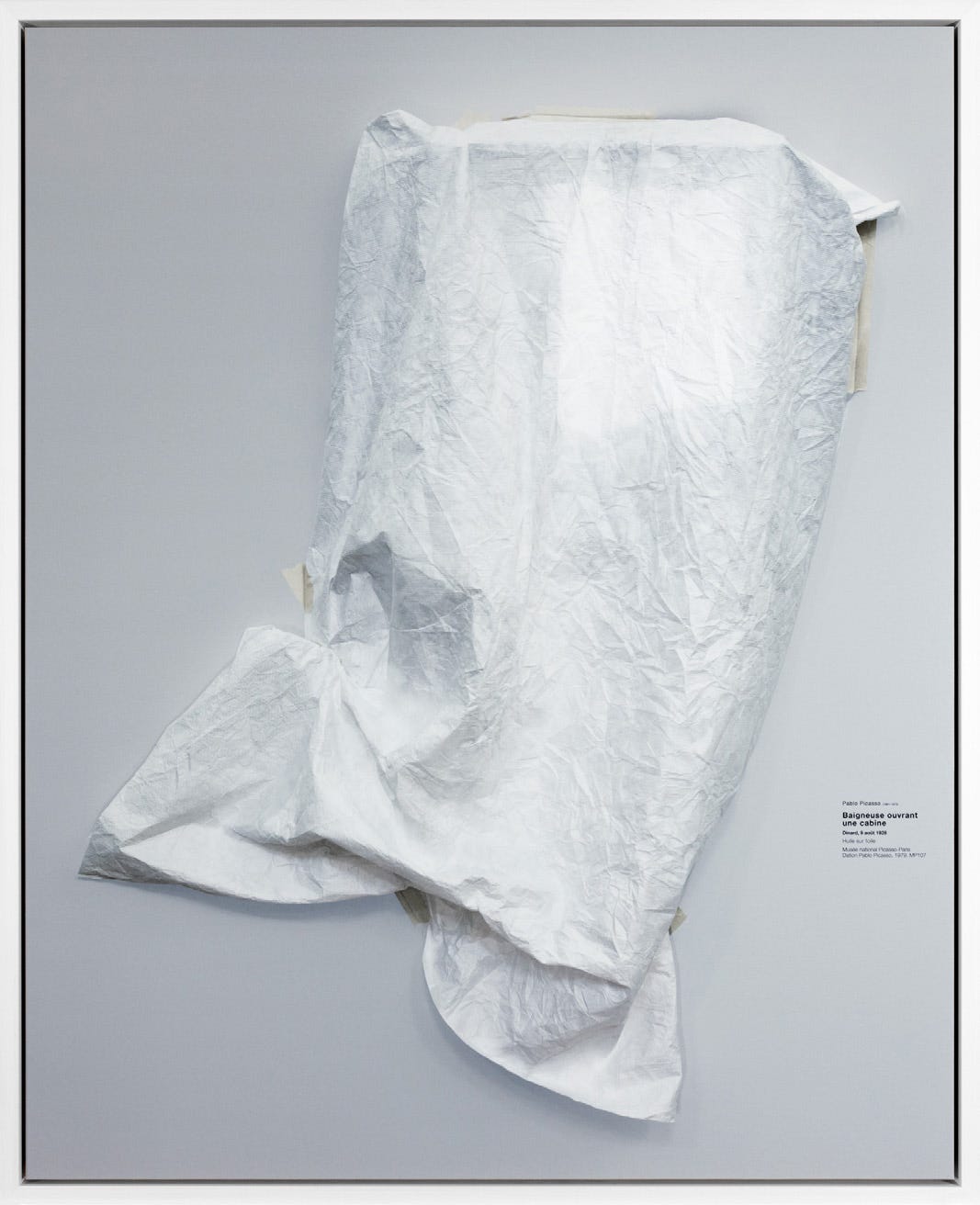

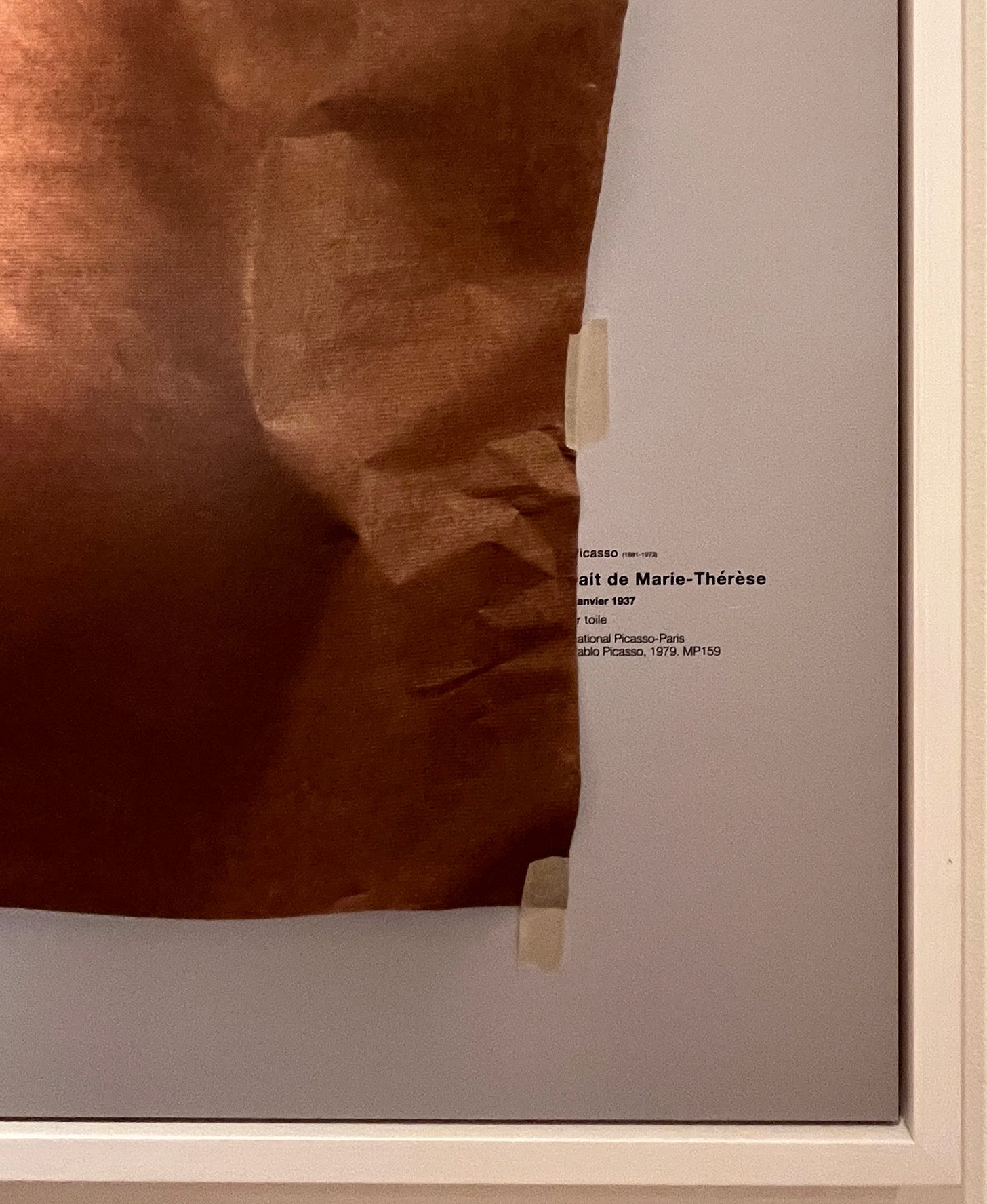

Which is not to say that Sophie Calle isn’t capable of taking a boring photograph. Between the “Autobiographies” and the “Catalogue Raisonné of the Unfinished” one will find “Picassos in Lockdown,” a series of pictures that Calle took in 2022 when she was invited by the Musée Picasso to make work “in dialog” with its collection of Picasso’s paintings. Claiming not to have the capacity to “face the overwhelming presence of his work” — ahem, bullshit — Calle only accepted the invitation once the Picassos were covered for protection during the Covid-19 lockdowns. She then set to work photographing the paintings, now “less intimidating” because “wrapped, hidden, like phantoms.”

Technically the photographs are very compelling. One gets the sense that a photo teacher from the local arts college could drag a class here and talk about qualities of the printing and the lighting and the exposure and the color balance and all of the other banalities of craft that photographers need to know how to execute but the virtuoso execution of which do not a great photo make. The most that one can say about the work is that they evince an attractive tromp l’oeil quality, given their shallow relief subject matter, and because the Musée Picasso’s wall labels look, in certain prints, as if they could have been applied by Calle to indicate the paintings behind the veils she was photographing.

In other words, because Calle is particular about the image character of the text that appears in her work, and because we know this about Calle, the labels here can look like they belong to the photographs, were put there by Calle, rather than belonging to the wall of the museum. It’s only when that text is covered by one of the painting’s protective coverings that the tromp l’oeil game is given up, and we see that we are indeed looking at straight, unadulterated photographs.

So there is something documentary and archival about these works, as well as something historical and personal, and that’s the most that one really wants to say about them. To go deeper into questions of photographic or archival documentation, of museum practice and procedure, of the history of the Musée Picasso itself, or of these particular Picasso paintings, or Calle’s relationship to them, and to this still-major figure in the history of modern art, one of particular import and presence for French culture and artists no doubt, or even to go into questions of masking and lockdowns and the pandemic, and the equal centrality of images to public health as to cultural policy, and into all the rest that any dutiful MA candidate in Art History or Curatorial Studies will no doubt take up in an effort to “work” on this work and to sound smart and signal intelligence to her peers and partners — to go into any of this would be both dutiful and anathema to Calle’s flight from boredom, because it would be boring itself.

Which makes these works good foils for thinking about Catherine Wagner’s photographs.

On Catherine Wagner

It is a testament to Catherine Wagner’s talent as a composer of images that she can make a film archive attractive. Her recent series of pictures takes as its subject the “Archive” of the Berkeley Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), one of a few facilities around the country that keeps safe the original prints of pre-digital-era films (that’s basically all films, for the youngs reading this). What this looks like in practice is canisters. Lots of canisters. Metal and plastic canisters with handwritten and embossing-tape labels all stacked on industrial metal shelving.

As with Calle’s “Picassos In Lockdown,” these pictures will tempt the academic initiate with their discursive generosity. The titles write themselves: “Stacking Desire: Catherine Wagner’s Archival Excesses,” “Cool Storage: Institutional Voyeurism in Catherine Wagner’s BAMPFA Series,” “Canistered! The Closeting of Analog Film,” “Nice Racks:….” — okay, decorum dictates I stop there.

But there is a sense in which these pictures do want or need to be written about, that their natural home, in some sense, is to illustrate arguments that want to make some case about the obsolescence of media, about the end of the machine age and the rise of digital and AI technologies, or about the material vestiges of Hollywood’s colonization of our collective imaginations, or any of the other topics that the “disciplines” of Archive Studies or Museum Studies or Film Studies might generate.

As if sensing this drive towards their becoming illustrations, Wagner doubles down on what she does best, and that is composition. Not only are the images carefully composed (again, the craft of photography is front and center here) but their contents are too. Apparently Wagner was granted the liberty of moving canisters around to create stiller-than-still lives of shape, color and arrangement, which she has done, though exactly how and in which photographs is never wholly clear.

The canister labels offer Wagner other compositional opportunities too, some times as piquant poetics for her photographs’ titles — Flash Attraction, Desperately Seeking Wanda (2024) and How to: Save a Marriage/Make a Monster/Succeed in Business (2024) are the two most obvious examples here — other times as pure polysemy, as with The Leaders (2024), which photograph so invokes a racial subtext under the guise of plausible deniability (“No, I just found them that way!) that it unmasks composition for what it so often ends up being in photography: opportunism.

I come away from these photographs asking a question I don’t find myself asking about Sophie Calle’s work though: Who wants these pictures? (I’m so taken in by Calle’s stories that I don’t even think to ask.) There are academics who will want Wagner’s pictures to illustrate their ideas. That much is clear. But those academics are fine with a reproduction, not the “genuine article” as they say. I suppose hard-core film fanatics will want them. BAMPFA will likely have to buy one (kind of a scandal if it doesn’t, no?). Adrian Lyne directed both Flashdance (1983) and Fatal Attraction (1987). He’s still alive. I’d give his people a call.

I understand how these photographs are part of Wagner’s own enduring interests in institutional architectures of one type or another, and as such they speak to that project and its reflexive relationship to art’s governing institutions, which, again, would seem to be the audience Wagner has in mind when making her work — i.e. the museums. But those institutions will take them into their collections as “Wagners” most likely, as tokens of that larger project, which undoes their bid to be something more than merely autonomous. Perhaps that’s fine. I’m just not sure what or how to think about it.

I had the same question about the series of photographs of Disney theme parks, which Wagner shot in the 1990s but only printed in 2021 and is showing now alongside the film archive. These too are great pictures. The low contrast black-and-white prints conspire with the parks’ own theatrical (a)historicism to present pictures that step out of time. Even for someone who was taken to Epcot Center as a child in the 1980s, Wagner’s photograph of that iconic geodesic sphere makes it so clinical that I didn’t feel a tinge of nostalgia.

Curatorially, it’s a great pairing, the Disney Parks and the Pacific Film Archive. And because of it, again, an entire academic discourse suggests itself. Like Calle’s mother, I’m already bored.

Claire Bishop has done a masterful job of tracing this contemporary aesthetic in her book Disordered Attention: How We Look at Art and Performance Today (Verso 2024).

I’m aware that there is an entire image/text discourse at work here, one that might begin with William Blake via W. J. T. Mitchell, who has made his entire career exploring the intersection and interdependence of these two terms, even as “image” remains the question while “text” is taken as a given. See Mitchell’s collection Image Science (Chicago, 2015) on this and other topics. This is not to discount all that has been said by and about Roland Barthes on the “Rhetoric of the Image” and other tracts, not to mention Michel Foucault’s little book on Rene Magritte. For perhaps the definitive account of “Sophie Calle” as a total construct see Yve-Alain Bois’s essay “Paper Tigress,” in the exhibition catalogue Sophie Calle: M’as-tu vue (Prestel, 2003), which accompanied Calle’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou.