Always Romanticize!

An unsolicited entry into the debate over the "new Romanticism" and what it means when it comes to the cultural politics of contemporary art.

“Romanticism is surely not political in its initial inspiration, yet ultimately it too is forced to concern itself with questions of politics, even if only to exploit or to bewail. Indeed, the disgust with omnipresent political activity is the greatest incentive to romanticism.”

— Judith Shklar, After Utopia: The Decline of Political Faith (1957)

Extremes and Margins

The playwright and essayist Matthew Gasda characterizes Romanticism as an “art at the edge of the volcano,” and he questions whether any of us in the present are truly prepared to live life the way the Romantics did or whether we would even want to. “Stated frankly,” Gasda writes, “Romanticism is genius plus criminality in an attempt to make the outer world resemble the inner world — beautiful, wild, insane, primitive and unconscious, and yet highly refined at the same time.” But, he goes on:

I think it’s important for us to consider whether we really desire to embody chaos, rebellion, insanity, and whether the belief or intuition that an art requires that dose of poison to achieve greatness is a productive one. And whether, in final calculation, our comfortable, safe, and predictable technocentric lives have rendered it fundamentally impossible for us to follow the path of Byron, Shelley, Rimbaud, Wagner — to cast our bodies and spirits into the volcano of modern civilization.

The philosopher Samuel Kimbriel, one of Gasda’s recent interlocutors and a self-proclaimed neo-Romantic, is skeptical of Gasda’s skepticism. The laptop class may be alienated from the fullness of life as it was apparently lived by the Romantics, but this does not obviate the neo-Romantic’s imperative to lean into the “tension,” which the Romantics both embodied and dramatized in their own lives and works, between the “immanence” of one’s lifeworld (its fraught politics, its soulless rationalisms, its staid mores) and the “transcendence” of that immanence (in Art, or God, or Love).

Both Gasda and Kimbriel agree that a Romantic metaphysics is not accessible without “embodiment,” that is, without casting “our bodies and spirits into the volcano.” For Gasda, that capacity for transcendence is “rooted” in what he observes — for Shelley and Byron in particular — as living lives infested with “venereal disease, sin, daring, fighting, suicide,” as “pushing the body,” and so one’s art, “to extremes.”

Kimbriel also sees Romanticism as a “way of life.” But Kimbriel holds that Romanticism cannot be reduced to merely “living turbulent lives.” It is an “intertwining” of life and thought, or rather life and art, life and creation, “as working out a tension” between the immanent and the infinite, while remaining humble to the experience, even submitting to it. The Romantics, Kimbriel holds, are “explorers” of the “boundary conditions,” of the margins of life as it is given, but ones with the capacity to return with wonders in tow and reports of their strange and unbelievable discoveries.

Romanticism Left and Right

I begin with Gasda and Kimbriel because their’s is the most recent exchange in a debate about the resources that the legacy of European Romanticism might or might nor provide us today for working through the cultural malaise that has hit Anglophone and other lands (or at least laptops) after a decade of plague, populist uprising, and techno-dystopian acceleration. And though both Gasda and Kimbriel consider Romanticism in its 19th-century flowering as a move against the politics of the day, against “factions” (Kimbriel’s word) and ideology, their assessment of the resources that Romanticism might provide reveals that what is really on offer is not ideology or its Romantic rejection, nor is it techno-rationalism, perhaps of the “abundance” variety or its cultish other, but rather two different Romanticisms, one Left (Kimbriel’s) and one Right (Gasda’s).

That Dean Kissick’s article “The Painted Protest” is considered an entry in this debate is helpful, as one of its strengths was to have staged exactly this schism, though it doesn’t do it in these terms. Far from simply offering a Romanticism “or something like it,” as I said at the time of its publication, or a Romanticism of the “mysterious,” as it has been labeled by the good folks at Wisdom of Crowds (who could be said to be hosting this Romanticism debate) — or no Romanticism at all, but rather a return to Kantian “purposelessness,” as the critic Becca Rothfeld holds — what Kissick narrates as a sequential episode in recent art’s aesthetic evolution can be read as a diagnosis of two contemporaneous modes of art making, each of which is romanticized by its partisans.

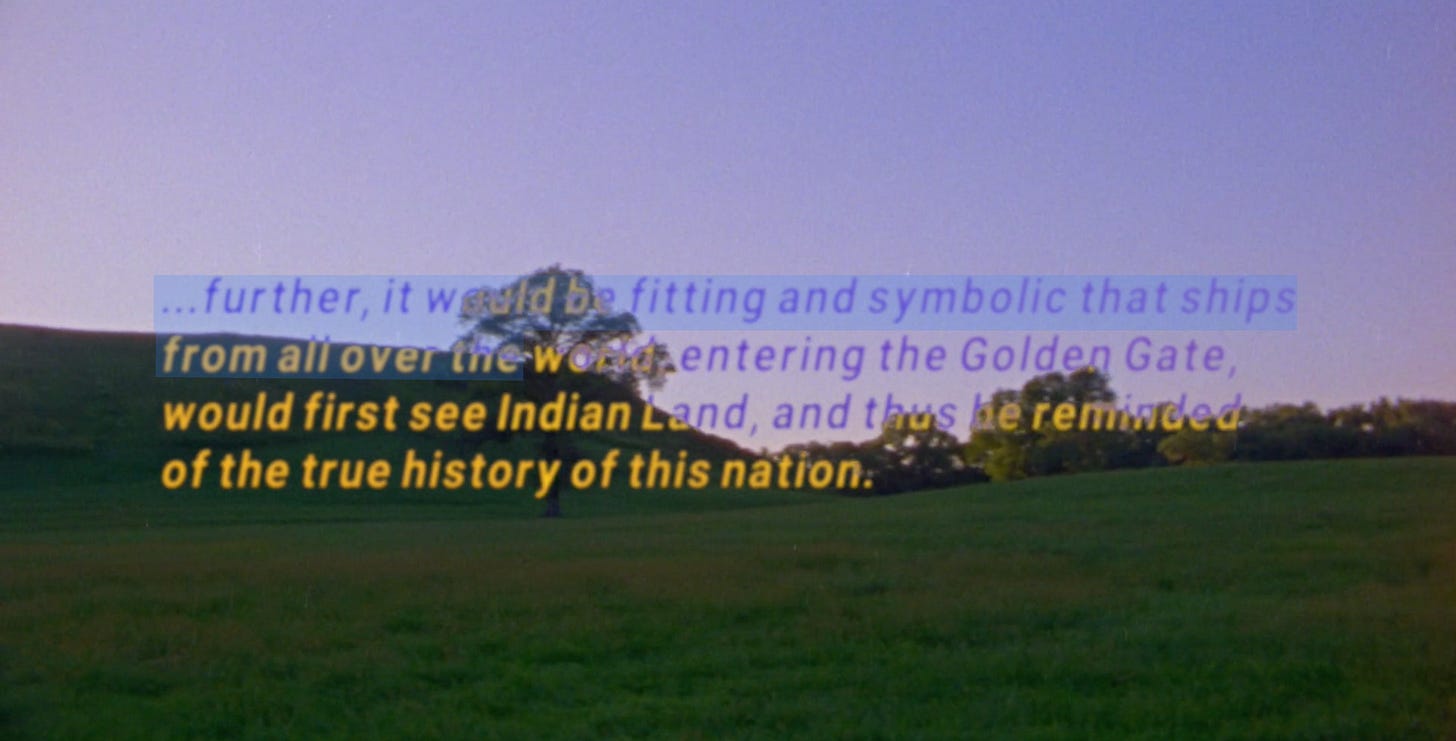

As Kissick wrote, all of the big international biennial exhibitions of roughly the past decade “have embraced overlooked artists from the twentieth century and exhibited recycled junk, traditional craft, and folk art. Their press releases have heralded the reclamation of precolonial forms of knowledge like indigenous thought and magic.” And what these exhibitions “suggest” is a

missionary zeal in reverse: rather than crisscrossing the globe and stealing the natives’ souls with cameras, curators now bring painted images of more primitive ways of life back to the disenchanted West so that viewers might be healed by their embodied knowledge, or otherwise access a direct link to the time before the Fall, to a paradise unspoiled by Trump, populism, Silicon Valley, globalization, modernity, the Enlightenment, capitalism, colonialism, nationalism, whiteness, linear time, and the Agricultural Revolution. Our god might be dead, but there is a wish to rediscover other, older gods.

What was often dismissed as Kissick’s rough treatment of the politics of identity masks a cogent understanding of what “resistance liberal” (Rothfeld’s term) institutions and their denizens romanticize as more innocent “ways of life” or salutary “knowledges.” When viewed through the lens of Kimbriel’s “tension,” we can see that what, on first glance, would seem to be the least likely inheritor of the European Romantic tradition, does in fact look nothing so much like our establishment cultural institutions’ romanticization of indigenous artists whose practices lean into their “immanence” and its promises for our “transcendence.”

Left Romanticism

It so happens that Native American artists are disproportionately represented today in American museum exhibitions. The estimable art critic Ben Davis has done the quantitative work to show which artists are getting the “most play” in museums each quarter, and as of March 2025, of the six artists that top his list, three put their Native American heritage at the forefront of their practices.

For example, of Cara Romero (first on Davis’s list), Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of Indigenous Art Jamie Powell explains that Romero’s “photographs speak to the importance of utilizing place-based and ancestral knowledges—or what Romero refers to as the ‘original instructions’ we’ve received from our ancestors—for building strong futures for Native and non-Native peoples.”

Of Rose Simpson (number three on Davis’s list) at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Curator of Contemporary Art Nadiah Rivera Fellah explains that Simpsons’s “large-scale sculptures represent a bold intervention in colonial legacies of erasure of the identities and ways of life of Indigenous people. Her work asserts a pride of place and belonging on land where Native residents have historically been forcefully dispossessed of their territories and cultures.”

For Sky Hopinka (fifth on the list), the Berkeley Art Museum and Film Archive says on its website that the artist’s film Sunflower Siege Engine “offers a meditation on resilience and belonging,” and that “Hopinka reminds us that the land and its histories hold both wounds and wisdom. In the artist’s words, ‘Being decentered from a land and a home burdens many of us. . . . It’s hard to parse out the pain of the elders and pain that’s your own. . . . Intergenerational suffering becomes a transgenerational reckoning.’”

These framings of the contemporary Native American artist and their art fits well Kimbriel’s take on Romanticism as, first and foremost, a “way of life.” Like Romanticism, indigeneity doesn’t stand as an intellectual movement or a theory with a specific position on contemporary politics; it is given to exceed politics.

Second, it is at once “sociology” and “metaphysics.” Indigeneity is unthinkable without the legacies of dispossession and marginalization that mark out the Native American identity, defined as it is now by ideas of “survivance, resistance, and community.” But at the same time, its continuous appeals to “ancestral knowledges” and “wisdom,” grounded as these are in claims to the “land,” stand as a “metaphysical realism” (Kimbriel’s term), which purports to ask deep questions about, and offer deep answers to, the nature of the world and humans’ place in it.

And third, particularly when considered as a political aesthetic presented within the contexts of the American art museum, indigeneity, like Romanticism, is presented over and over again as illustrating exactly the irresolvable “tension” between the “terrestrial and infinity” (Kimbriel again); it leans into the immanence of being “decentered,” “forcefully dispossessed,” and in “pain” as a way of reaching for the transcendence of a “strong future” and a final “belonging” — for turning a “suffering” into a “reckoning.”

According to the ventriloquists of the American art museum, indigenous art and artists are uniquely positioned to explore the “boundary conditions” of contemporary life. On this logic, the logic of Kimbriel’s thinking (if not his actual words), they qualify as our true neo-Romantics.

Right Romanticism

This not to suggest that Native American art and artists are the only avatars of neo-Romanticism today validated by liberal cultural institutions. Any artists who approach their practice as a “way of life” at one level of intensity or another — from making it resolutely personal, an exploration of and mediation on the “artist” (I’m thinking here of someone like Enrique Martinez Celaya); to using art-making as a kind of procedure or protocol through and by which one’s art and life are organized as a life-styling endeavor (Tom Sachs would be an example here) — could be said to be operating on the neo-Romantic spectrum that runs between margin and extreme.

Gasda for his part believes that “what is best in the Romantics is the intensity with which they sought private experience — an experience they actively sought to create.” Perhaps what is different today is how the intensity of that experience must be lived in public, if not publicized. One need only look as far as a recent New York Magazine profile of the Gagosian-rep’d artist and gallerist Jamian Juliano-Villani (whose art, I must confess, I would not be able to pick out of a lineup) to believe that here one has a candidate for a Gasda Romantic in all of that idea’s glorification.

In Juliano-Villani, one finds an artist pushing her body to extremes of sleep deprivation, drug use (weed, ketamine, alcohol) and sin (“It is racist and misogynistic and embarrassing,” the artist Kim Dingle noted of Julian-Villani’s gallery-project O’Flahrety’s); one can only guess as to whether the degradations of venereal disease were ever part of the mix, but that seems besides the point.

This is not to dismiss Juliano-Villani or her art (which, again, may be largely irrelevant), it is only to show how she occupies a space on the spectrum that would appear to accord with both the renunciation of upper-class entitlements (though mom and dad are there to pick up the pieces when things get out of hand) as well as the aggrandizement of self-destructive behavior that characterizes the Romanticism of which Gasda appears both wary and enamored, but which cannot but be romanticized when narrated as a lifestyle — that of a “chaos agent” who keeps us “guessing” — as opposed to a more thoroughgoing “way of life.”

For that one might look to the work of Lionel Maunz, especially as it is narrated by the writer and critic Adam Lehrer. When Gasda writes that “A new Romanticism would not just question compulsive post-Covid safetyism, it would reject, laugh at, the entire civilizational premise of statistics-based reasoning and the securitization of the human body,” I think of Lehrer’s at turns withering and aggressive disdain of liberal pieties, in the art world and beyond; and I think of Maunz, an artist Lehrer admires if not celebrates, who for more than a decade has created sculptures and pictures that one would have to call “highly refined” but which take as their subject matter a violence and cruelty that one would also have to call extreme.

It is not that Maunz’s work is without precedent. There was a time in the 1990s when the abject was all that anyone within advanced precincts of art wanted to talk about. But in the intervening 30 years, the psychoanalytic theory that informed that moment expanded to become the cloying “trauma-informed” practices that enveloped not just art studios, but the art schools and philanthropies and cultural institutions against which it’s understandable that the neo-Romantic would set their shoulder if not their sights. But it is to Maunz’s credit that even this enervated social context is not worth exploiting or bemoaning. As he tells Lehrer, in response to a question about surrealism:

I'm also suspicious of surrealism. I'm not trying to show anyone anything. There's no revelation. There is zero communication as it's generally understood. I’m not trying to change your mind, I don’t fucking care what you think. This is a conversation with myself and a tiny handful of others. I'm really not trying to show ‘them’ anything; they just don't register. I wouldn't waste my time convincing. When I’m corrective, it's not for the audience. Surrealism is an exit, an opt out, a boring and sloppy gap in paying attention while pretending it's the exact opposite; it’s self-indulgent trust and relinquishment. I care too much about what I’m doing to get it that wrong…

Whatever else one might take away from such a statement, it is clear that Maunz is not entertaining a lifestyle. He is engaged in a “way of life” that has submitted itself to the imperatives of a way of making art that is as difficult to behold as it is, presumably, to make.1 This is certainly how Lehrer reads Maunz’s work:

Lionel doesn’t advocate for a political position in his work, but one can glean from the work where he stands. He seems to have an innate repulsion towards weakness, victimhood and entitlement. For one, his art is of an elitist paradigm. His sculptures require an exceptional level of craftsmanship and precision […] For me, it’s Lionel’s maniacal work ethic and supreme commitment to making art as difficult for him as possible that is ultimately more transgressive than the violent content and imagery that he trades in.

If Maunz is not explicit about his politics, Lehrer is about his own. If I describe Lehrer as a “resistance reactionary” it would only be to position his voice against the institutional one of the “resistance liberals,” the ones who romanticize indigeneity in equal measure to how Lehrer romanticizes Maunz’s art, which stages a Hobbesian “anarchism” — that way of life which is beyond, before, or outside of politics and its capacity to discipline raw power — as indigeneity’s mirror.

Romanticize or Critique?

Why we romanticize the art and the artists that we do is a good question. But the debate between some identity-based indigenous art of the margins and some other art of feeling or extremes that abjures politics or is beyond meaning is really no debate at all. It’s just the articulation of two versions of the same impulse to romanticize a politics we desire via the art that we advocate.

Acknowledging as much should force us to reconsider whether there really is anything in “the Romantic worldview that remains appealing,” as Becca Rothfeld writes. Rothfeld has written the best defense to date of how that worldview might serve us in the present. She is right to remind us that Romantics were not so quick to cleave the aesthetic from the political, the beautiful from the good. The blame for that bit of cookery — aesthetics: it’s all just a matter of taste anyway! — lies at the feet of Emmanuel Kant, whose three Critiques required the aesthetic to bridge the gap between “pure” and “practical” reason, between our individual intellect and our duties to others. Dividing the inside world from the outside world (“in itself” as Kant would hold) are our senses. And aesthetics became the means by which I could be assured that the thing I sense as “beautiful” is beautiful not just for me but for all who have the capacity to sense it. This is how the Cartesian “I think” could become Kant’s “We know,” with all of the responsibilities and duties that this entails. Kant called it a critique of judgement for good reason.

Yes, this separation of the aesthetic from practical reason, from politics, was intolerable to the Romantic mind. “It’s no exaggeration to say that the entirety of German Romanticism was an attempt to reunite” the beautiful and the good, writes Rothfeld. Schiller and Schlegel and Novalis were deeply invested in, if not politics per se, then at least a political aesthetic: “Their utopia,” Rothfeld states, “is a heady amalgamation of material innovation and high-minded ideals, which is to say, a work of art.”

But even if Rothfeld is ultimately sympathetic to some part of the Romantic worldview — she is still “glad that art can matter enough to wound and maim” — her nod in the direction of judgement is informative:

Sometimes—I suspect quite often—art fails aesthetically because it fails politically: James Baldwin argued that Uncle Tom’s Cabin is “a very bad novel”because of its “self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality,” and much the same can be said of the literature of resistance liberalism. But sometimes art is good precisely because its politics are bad: Portnoy would be a flatter character, after all, if he were a feminist. Sometimes art is good despite its bad politics, not because of them (Anna Karenina can withstand even the saccharine sections about the moral simplicity of peasants), and sometimes art is good despite its good politics (it’s only possible to enjoy the depravity of Dangerous Liaisons when you disregard its dutifully moralizing preface). If art and politics do not have a fixed rapport with one another, there is not much we can know about their relations in advance. Our only option is a careful consideration of each work in the wild.

Since I too am in the criticism “racket” (Rothfeld’s word), I co-sign this sentiment, but when I think about it, the “politics” here aren’t really being judged, they’re just understood. They’re organized as already good or bad. When viewed in concert with the work of art under consideration (“in the wild”), the result either adds to or subtracts from the quotient of goodness or badness in the art, or it doesn’t affect it at all. The point that Rothfeld is intent on making is that bad politics can make for good art, either “because” of or “despite” those politics. But the question I would want to ask is: Can a work of art change one’s politics?

For that one must feel, yes, but one must also be made to think. The problem I have with all of the contemporary romanticizing is it ends up leaving contemporary politics well enough alone, which makes it increasingly difficult to face, let alone challenge, those politics, or to find one’s mind changed about them. Critique, in its turn, does something different.

Rothfeld shows how when she sets her sights on the politics of resistance liberalism:

The problem, in part, was that resistance liberals evinced bad politics. Their smugness about their own righteousness was patronizing, at times even anti-democratic; their simplified worldview, in which Trump voters were evil and they were faultless, was Manichean; perhaps cruelest of all was their conviction that the symbolic currency of representation could take precedence over the bread-and-butter of material redistribution.

One might argue that here Rothfeld is certainly judging the resistance liberals’ politics, but on closer inspection again the good and bad of those politics (okay, mostly bad) is largely irrelevant to her critique that, whatever you may think about the aesthetics of those politics, with their insistence on the “symbolic currency of representation,” they did nothing when it came to an actual politics — that is, a policy — of “material redistribution.”2 Such is the actual “violent junction” (Rothfeld’s term) where aesthetics meets politics in an acute, critical observation — at least insofar as one could frame this as the former (representation) missing its turn and wrapping itself around the lamppost of the latter (redistribution).

That junction does not entail romanticizing the aftermath (this isn’t a Cronenberg film); it entails a critique of how it happened. After all, nothing wounds or maims quite as much as realizing that the art you make, or the art you admire, evinces a politics that you might otherwise abhor. But those are exactly the injuries that can change one’s mind.

There is a point to be made here about such a “way of life” in Gasda and Kimbriel’s thinking being one that is chosen, something that the artist wills for themselves, rather than a life that is dictated by circumstance. Certainly for the 19th-century Romantics, their “embodiment” has been given as self-inflicted, and so as a choice to be made, which accords with all of the later-day flowerings of radicalisms and avant-gardes which were watered by escapees from the jailhouses of bourgeois complacency and comfort that were wardened by their parents. It could be argued (and would be by progressive critics), that the contemporary Native American artist has not chosen their way of life, however, but has been subjected to it, conditioned as it is by the racially-motivated dispossession that pervades the history of U.S.-sponsored settler colonialism. It could also be argued (and has been by astute critics such as Christina Rees) that Maunz’s particular way of life might not have been chosen either, but is determined by the unspoken mysteries of childhood abuse, both Maunz’s own and to which he bore witness. Further reflection would have to contend with the contradiction between the specific and the general in such assessments, that is, whether group conditions can be said to determine the specificities of the person, and whether individual experiences, particularly in childhood, can be generalized into causal dynamics for entire class of adult behaviors (c.f. the DSM). Whatever the case may be, if the question is whether one casts themselves into the volcano, or is cast into it by circumstance, the answer is that the “way of life” that is the artist’s is and always has remained a choice, even when making art is romanticized as being that thing that artists do because they couldn’t possibly do anything else, which is and always has been romantic bullshit.

I feel compelled to note that the critic Walter Benn Michaels has been mounting this critique for decades.