Problems of Decoration; or, Some Art in San Francisco Part 3

Liam Everett & Zheng Chongbin @ Altman Siegel; Nancy White @ Romer Young

Preamble

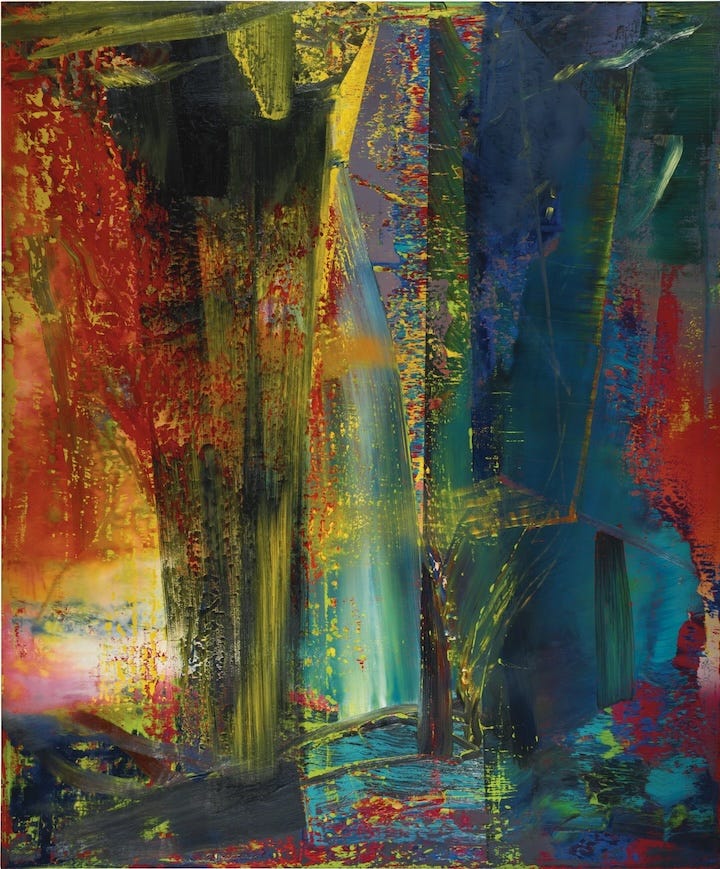

Visiting the German Art After 1960 exhibition at SFMOMA, after seeing a trio of contemporary painting shows in town, left me wondering the following: How can any painter who walks into the first two rooms of Gerhard Richters go back to her studio and choose to paint? How are you not faced with the fact that Richter has already done, in some capacity, in some manner, what you might be thinking about trying to do in your own work? Doesn’t every artist who meets that work end up like Ed Harris (playing Jackson Pollock) fretting and complaining to Marcia Gay Harden (playing Lee Krasner) about Picasso (playing himself) already having “done everything!”?

Well obviously not, because paintings and painters persist, but it’s an honest question that persists too. When history threw down its gauntlet and declared painting dead, Richter said, in good German fashion: “No, not dead. Just dying. As are we all.” He then went to the studio and gave us work that feels resolutely contemporary while also running through all of the tropes of painting’s past: he gave us landscape, portraiture, and still life; he gave us photography, the readymade, the monochrome, the archive; he gave us figuration and abstraction; he gave us installations art (Eight Gray, 2002) and decorative art (the Cologne Cathedral Window, 2007); he gave us history itself, via the Red Army Faction, German reunification, a family history of National Socialism (how’s that for identity concerns?) and 9/11; and — and — he gave us big, beautiful trophy decorations, canvases that luxuriated in the viscosity of paint and pigment and material and the (literal) sweeping gesture. And like the waters of the Lethe, these works made us forget everything else, except perhaps how much they fetched at auction.

That was exactly a decade ago, in 2015, when Richter’s Abstraktes Bild (1986) set a sales record ($46.3M), marking perhaps the pinnacle moment of what the late Walter Robinson named “zombie formalism.” He wasn’t referring to Richter’s work, just everything that was surfing in its wake, where process and material and surface effects set the odds on whether this work was actually pushing painting towards new horizons or just returning it to shore, like some superyacht on the “milk run” in the Mediterranean.

By naming this aesthetic Rumpelstiltskin, Robinson gave everyone the leverage they needed to call its bet. And call they did. The following year, Kerry James Marshall’s Mastry opened at The Met and Dana Shutz painted a picture of Emmett Till. Who was doing the painting became as important as what was being painted, in some cases more so. And so the magic of spinning canvas and pigment into gold passed into different hands, and new bets were placed on the line.

On the Decorative

Whatever you may have thought of the work that was being valorized by the market and the institutions over the past decade, what was clear was that there was a rationale for it. The value of that rationale, and thus of the art that has been validated by it, is the topic of continuing debate, as is whatever ideology might succeed the “successor ideology” that gave that rationale its authority. But one thing that has remained consistent for the past twenty-five years is that much painting wants nothing more than to be decorative.

One way of thinking about this is a follows: If the “painting of modern life” (modern art, broadly speaking) set for itself the goal of taking up residency within the museum — where it could be compared to the great works of the past, could work through its anxieties of influence, could challenge the very capacity of the institution to contain its aesthetic and political positions, and could imagine itself to shape both public and elite tastes — most “painting of contemporary life” (contemporary art, broadly speaking) sets for itself the goal of taking up residency on nothing more than a wall, the main virtue of which being that it is better than languishing in storage and marginally better than the phantom zone of a screen.

Many of those walls remain museum and biennial walls of course, but what those walls represent today, when their cultural authority is facing a crisis of legitimacy, is different than it once was. Thus other walls beckon, many of which no longer occupy the lower reaches of that status hierarchy which every artist keeps in mind when seeking opportunities to show their work. There are hotel and restaurant walls, the walls of commercial real estate and corporate offices, of social clubs and co-working spaces, of private foundations and luxury homes and faux chateaus. If one needs a single avatar of such flattened hierarchies, just consider that one of the most significant dealerships of art today, Hauser & Wirth, has replicated with great success exactly these types of places – high-end restaurants, country retreats – as a means to market its artists’ wares.

In this world, painting’s primary function is to adorn, and in adorning, it signals settlement, presence, a general investment of human agency — not on behalf of the artist, but on behalf of the space it embellishes and that space’s managers and inhabitants. (We could ask: Why is it that few things make us more uncomfortable than an empty wall?) If throughout most of the 20th Century painting’s status as decoration was a condition to be resisted, rebuffed, reconsidered, today in the 21st it is, resignedly perhaps, painting’s raison d’etre.

On Liam Everett

At least this is the sense one gets from a great deal of the painting that one sees in the galleries. Take a recent show of new works by Liam Everett at Altman-Siegel’s storefront on Sacramento Street: It would be uncharitable to dismiss this work as rehashing Richter, as this is just what many artists might be condemned to do. But the echoes are unmistakable, as is the general visual pleasure that one gets from looking at these canvases. They are indeed nice to look at; it would not be wrong to describe aspects of them as beautiful — certain passages, certain color contrasts, certain washes of pigment. But what one wants to say of them is that they are “pretty” and leave it at that.

Putting to the side the entirely overwrought descriptions of what motivates these works — the artist’s interest in “quantum biology”; the energy transfers across cellular membranes that give off “light”; the fact that water is an energy conductor and is integral to human bodies and paintings alike — one is left with just the fact of the paintings themselves, and how they look, which again, is a lot like work Richter was making 40 years ago, or, for that matter, like Jack Whitten was making 50 years ago.

It’s telling that these paintings are paired with two sculptures by Larry Bell, whose experiments with colored and smoked glass configurations are signatures of the Light & Space moment of the 1960s. If the Bells are deceivingly simple in form, the complexity of their effects are immediately apparent: prismatic refractions, mise en abyme, reflections of one’s self, the walls that surround, the sculpture turning in on itself and outwards at the same time. Then all you need do is take step to the right or left and it all shifts. Attention and “noticing” is rewarded. And perhaps, in walking away, you see or let in a little bit more of what the world offers up to vision. This is what this work is about, and why their author has a place in the history books.

Everett’s works don’t work like that. One suspects they want to, which is why the Bells are there, as if to suggest they share the same concerns. But they don’t. I would go so far as to say that the Bells are bad for Everett, as they demonstrate everything that the paintings fail to do in terms of the light, energy, and the acute attention that they wish to court. The question we’re left with is for what walls are these destined? What interior will they “go” with? Which decorator’s eye will they catch?

On Zheng Chongbin

There is something similarly compensatory at work in the moving image installation that accompanies Zheng Chongbin’s large pictures at Altman-Siegel’s main gallery, insofar as the installation serves something of the same purpose that the Bells do for Everett: what’s on the walls wants to be explained in part, or rationalized in part, by a different art form, in this case what’s on a screen.

What’s on the screen, actually three screens, is The Branch of the Folding Tree (2025), a roughly seven-and-a-half minute loop of imagery that is difficult to parse but appears at turns liquid and mineral and organic. Adjacent to this is a slowly rotating x-ray scan of some organism that looks crustacean-like. The screens themselves are layered as well as juxtaposed, such that light from the projections (some front, some rear) reflect and interfere with one another, which further adds to the difficulty of parsing what one is seeing. The work is described as entailing responses to the motion or actions of its viewers, but what those responses are, how they manifest in the space or in the contents of what one sees, was lost to me. What one takes away, though, is that there are physical and material processes at work here — causes and effects — and those processes are complex and generative, like embryogenesis or crystallization, ways of making form that don’t entail an intention.

And that, presumably, is how one is meant to read the pictures too. Chongbin has a way of working with ink and acrylic and pigment on specialty rice papers that generates very satisfying effects, the results of which can look like alien geologies or highly magnified crystalline surfaces. As works of art, these pictures are the result of a dynamic process that includes the artist, but the conceit is that the process the artist sets in motion, like some chemical reaction, is as much the author of what one’s sees as is “Chongbin.” In this, the work offers a kind of fantastic realism, one that connects to Song Dynasty landscapes as much those by Frederic Edwin Church.

But as much as I do find a higher intelligence at work here than in Everett’s pictures (which also shore themselves up through subscription to a kind of scientism), once these observations are made, once the process has been acknowledged and the realism registered, what are we left with? What is the artist working through? Not a line of research bent on finding answers to a specific pictorial puzzle, to figuring something out about picture making. Not even really a method, a way of doing this work that affords the exploration of an entire space of creation. I just can’t shake the feeling that what we are left with is a series of effects, the causes of which may be more or less initiated by the artist, more or less a function of the physics and chemistry of particular materials, but which have little to do with whether those effects are themselves worth attending to.

What we’re left with, in other words, is this question: Do they look good (or “cool” or “interesting” or “based” or whatever)? And when that’s the question — the question of how something looks more than why it looks that way — we’re again reduced to debating the work as decoration.

On Nancy White

I think Nancy White does something different. It may be a small observation to make but White’s works want to be part of the wall, or if they don’t exactly want to be part of it, they do want to get close to it. Each work is acrylic on linen stretched on a fiberglass panel that is roughly a centimeter thick. One gets the sense that the stretcher panel is already a compromise, that were there a way to get the linen directly on or in the wall, White might do that. The point seems to be do away with the third dimension, even while putting up with it. Another point to make is that, in this “doing away by putting up,” White accounts for the work’s destiny as decoration, and so deals with it.

Not defeats it, but deals with it. Acknowledges it. Recognizes it. Understands it as a major condition of the painting of contemporary life. And gives this to us to see. It’s why the question of how her paintings look (good!) does not outweigh the question of why they look the way they do.

In contrast to Everett and Chongbin, White’s painting involves her own considerable intelligence exerting control over every dimension of the picture. Shape, color, arrangement are not effects of a process, the results of which might be judged better or worse (“How’s this look?”); they are the results of a procedure, the judgement of which is internal to the procedure itself; indeed, it makes the procedure what it is (“I am doing this because it is what I want to show”). It’s like the difference between gardening and performing neurosurgery: how you feel about the result (“This looks good”) is irrelevant when the point is to restore sense itself (“I can see”).

Similar to Chongbin and his rice paper, White treats her linen as more than just a ground. The pigments are in the linen, which reinforces the fact that these works present a single surface, even as they appear articulated, colored, composed. (Helen Frankenthaler is the touchstone here, not Richter) The materiality of the work is present, but more as a means to emphasize that this is a made thing, a painted thing. How it is painted is transparently evident, which leaves us asking why it looks the way it does; its materiality is not the point, it’s how we get to the point — not something we look past, but the mechanism of looking itself.

Something of the same case can be made in terms of White’s compositions, which are not regular, nor patterned, nor repeated. It’s a staple of quite a lot of contemporary painting in the high decorative mode that an artist will select a “theme” to structure their composition and then repeat it across a number of design or color schemes. Perhaps they do this to limit the decision making required at the outset of a painting campaign. If the subject matter can be set in advance, then other dimensions of the painting can be attended to. (I heard the artist Senon Williams describe a recent series of works in just this way.)

In case of White’s paintings, however, where there is no pattern or repetition, composition becomes the sign of White’s decisions, which is to say, of her intentions. If there is a process to be understood, then, it would be akin to understanding White’s own mind — in other words, it would be akin to understanding what she means to do in and with her paintings, which is the same thing as understanding why she makes them, which is the same as understanding what they mean.

On Reflection

About three quarters of the way through writing the above I became aware that I had stayed away from using certain terminology, such as “abstract” or “abstraction” as well as “the market.” Once I noticed this I decided to stay with it, as I think this kind of broadly descriptive or labeling language doesn’t do any work anymore. Our need to identify work as “abstract” vs. “figurative” or “representational” would seem to belong to a past that isn’t with us any longer — these terms aren’t analytical. That they lend themselves so well to the discourse of identity — e.g. “Black figuration” — is another reason to reconsider their usefulness today.

Discussions of the “market” are all too often vague approximations for some more specific commercial or transactional mechanism at work in the world, one that can’t be reduced to mere “capitalism.” My attending to something like “decoration” or the “decorative” now appears to me as an attempt to shift the frame somewhat, not to pull it back or to zoom in, but to consider what kind of art is being made under contemporary conditions in which images and history and the status of the artist’s intentions for their work are very much problems or questions that need to be dealt with.

I’m well aware that to speak of the “decorative” is to invoke the decorative arts or even the applied arts and that moment in the 19th Century when the whole point was to fashion a distinction between what was “fine” and what was something else. But does anyone truly think that such distinctions are worth holding onto today?

The mythology of art’s autonomy from the commercial sphere, the idea that to secure its sense of self was to defeat its status as a commodity, just doesn’t seem to apply to the great number of things that artists do at present that would seem to hold our attention as “art” but which also fit easily into the larger flows of economic activity. Much as literature today is just one genre of fiction writing among many, much of what we once thought of as fine art may be — I would argue is — just a genre of decoration. How fine art evolves within that designation, how it deals with decoration, is a problem with many solutions, some stronger, some weaker. Assessing which is which is what criticism is for.

A painter’s note about the idea of decorative art…you said “painting’s primary function is to adorn… not on behalf of the artist, but on behalf of the space it embellishes..”

Perhaps it’s a question of who you think defines the function of the tool, and wether you’re willing to accept the ‘collector/curator’ as a responsible user. Most of us don’t intend to make decorations, but even the most ‘based’ works - an old Murillo drop cloth - become decoration when used wrong. Art is an instrument, zuhandenheit, ready-at-hand, and must be used as art, as something to interact with perceptually and contemplate openly. But, in the same way Kosuth used a chair as art when it’s better for sitting, art can be used poorly, as a proxy for a collector’s taste or an illustration of a curator’s intellect…as a decoration. Decoration is a warped mirror, a reflection of desire.

Yes, truly Great art has such a presence that it’s functioning as art regardless of how you intend to use it; wether it’s shouting a manifesto or whispering sweet nothings, we stop when we walk by, and we listen. That’s great art, but good art, the majority of what even great artists make, requires a good listener and a desire for discourse. It’s powerful, maybe even great, if you’re using it right. The fact that it can be talked over, used as arm candy, as the proof of a point, isn’t the fault of the object. It is, after all, just a thing.

The good news is that in its dormant, decorative state, good art doesn’t loose its ability.

It can function again, as soon as someone’s willing to use it as art…that’s not a bad bargain!