Phosphorescent Quotation; or, Some Art in San Francisco Part 7

On "Lagrange Point" at Slash, Tyler Ormsby at Altman Siegel, and Isaac Julien at the de Young

Lagrange Point at Slash

“Phosphorescent quotation.” That’s how Hugh Kenner described a shift in the strategies of satire in the 1950s. Prior to Dwight Eisenhower’s administration, satirists had to isolate certain traits of their targets and exaggerate them. With Eisenhower, Kenner writes, “it was sufficient to quote him verbatim.” The same would go for Kennedy, such that, with the 1960s well underway, Kenner observed that a “wide range of phenomena ‘parody themselves’.”1

Kenner’s term came to mind as I was driving home from seeing Lagrange Point at Slash, a group exhibition of seven artists curated and with work by a “collective” of three others calling themselves Ninth Planet. Lagrange Point is a consummate exhibition for our contemporary moment: it presents a magisterial opportunity for phosphorescent quotation, insofar as it manages an unbearable conspiratorial balance between utter sincerity and total bullshit.

This is not the “Lagrange point” that Ninth Planet imagines it is invoking, of course. As the collective articulate it:

A Lagrange Point is a relationship of equilibrium, a region in space where the gravitational forces of two celestial bodies create a state of suspension. It is a place of stillness between immense forces, and a vantage point for recalibration. The exhibition borrows this concept to explore thresholds and transitions of knowledge, power, and perception in relation to UAP and broader ideas around non-human intelligence.

That bit about “UAP” is germane because it was the promise of the Pentagon’s full disclosure of what it knows about “unidentified anomalous phenomena” that sparked the very “formation” of Ninth Planet, which began,

with a walk through the streets of New York City in the summer of 2023, just before the U.S. congressional hearings on unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) and non-human “biologics.” Recognizing that we were likely on the brink of “official” disclosure of non-human intelligences interacting with contemporary human civilization, our collective formed, with an aim to wrest the narrative away from military, governmental, and corporate ownership. Rather than reinforcing systems of control, we seek to illuminate what falls outside the frameworks of global political power structures: the lived experiences, histories, and cosmologies that have long acknowledged and incorporated encounters with the unknown.

Putting aside the grandiose incoherence of that mission statement, one can take this as a lesson in the perils of jumping the gun. What does Ninth Planet do now, one has to ask, with the knowledge that the entire enterprise of US-government-driven teasings and cover ups of UFOs and alien contacts was just one big disinformation campaign going all the way back to the Eisenhower administration? Probably very little, because the conspiracist mindset doesn’t seek truth, just the perpetuation of its own narcissistic commitment to knowing what you don’t, or won’t. As Ninth Planet point out:

Though UAP discourse has returned to the public sphere, the discussion remains entrenched in restrictive paradigms of inquiry such as governmental hearings, military records, and Hollywood documentaries. These narratives treat the unknown as a technological threat, a sanctioned and sensational framing of the fringe, or a puzzle to be solved. Lagrange Point is not separate from that conversation but intentionally positioned just beyond its gravity well, where epistemologies shaped by Indigenous cosmologies, queer futurisms, and alternative ways of knowing are centered.

What began as a promise of galactic-scale revelation, one that will set us free from the military-entertainment complex of false consciousness that enslaves us, ends as the spectacle of over-educated artists flailing around in the technicolor ball-pit of progressive art-world clichés.

The works in the show are far from that, however (though their descriptions certainly are). And this is why Lagrange Point really does have something to offer. One can’t tell whether the highest of high-minded rhetoric that accompanies every work in the show is meant to be taken seriously (I mean, it must be? I really can’t tell).

The entire “conversation” here is about contact with the unknown, which is self-reflexively acknowledged to run in the direction of conspiracy. How do we know? Why else include selections from the “Archives of the Impossible,” a collection of materials housed at Rice University that document accounts of UFO sightings, abduction narratives, and other ephemera described as a “pattern” and a “murmur” of something that “exists beyond established frameworks of knowledge,” if not to make the case that contemporary art functions the same way?

Art is that thing that’s beyond language, beyond description, beyond the rational sensibilities and faculties that we regular employ to make sense of the world. At least this is what we’re so often told. So why not the UFO conspiracy as epistemic model? If all “other ways of knowing” are equal to, or better than, the much-maligned Enlightenment rationalist legacy, and art has always been orthogonal to that legacy in one respect or another, then the epistemology of conspiracy suggests itself as the arch contemporary mode of thought (and politics) today.

Lagrange Point offers just this: in a world where the purposes of art — what it is, and why it might matter — have become questions of no small import, but also ones of seeming irrelevance to the vast majority of people who could care less to engage with art in any of its conventional manifestations, what better frame to place around such questionable practices than that of conspiracy. If you don’t know anything about art, don’t worry, because no one really does. So just hold on to that sense of perplexity, of not knowing. Dwell in it. Make it the operating system of your worldview. Do your own research. Just ask questions.

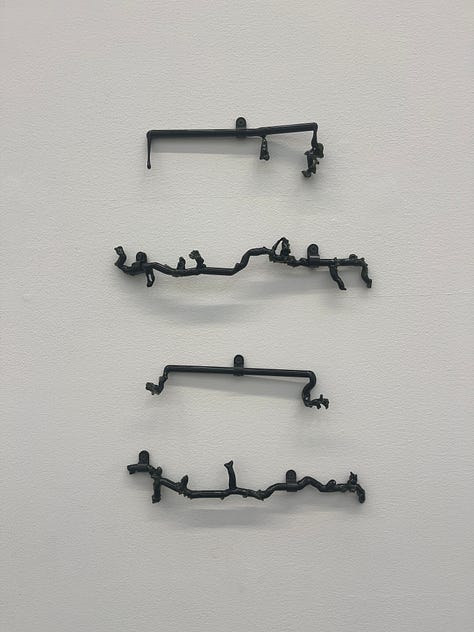

This would all just be intolerable bullshit were the gestures in the show, which is to say the things that have been made for it and that are included in it, not nearly so sincere. The art here has been made with the greatest of care, in the greatest variety of mediums: from a highly-wrought video animation with a vague environmentalist narrative; to sculpted glass figures that evoke strange organisms (as well as what looks like evidence from an explosion in a neon-sign fabricators); to small ceramic sculptures, onto which are heaped every imaginable commonplace of southwestern US craft traditions and the people who make them. There is a manifesto. There are embellished crackers (for a space Eucharist?). There are some glittered-up and very-scaled-down Nazca lines. There is prehistoric bacteria in vacuum-sealed bags.

Every works’ wall text is larded up with layers of reference to the “unseen,” the “unknown,” the “other worldly” or “extraterrestrial” or “ancient” — everything and anything that might challenge our assumptions of epistemic access. And yet, to be perfectly honest, it’s all very well done. No one is shirking the details here. The work that is the arguable centerpiece of the show, Whit Forrester’s The Electric Universe Theory (2022), appears at first glance like a another of those egregious examples of artists working within the medium of the art market’s perfidy, but its bicameral, platonic form, its elemental materials, and the little electrodes and stim pads attached to it, create just enough of a technical suggestion to make one suspect, if not believe, that something else is going on here.

What that something is might matter to Forrester, and to Ninth Planet, and so it should matter to us, if we want to understand what the work is about. But seeking answers from the artists, verifying their truth claims, deducing their meanings from the results of their actions — i.e. from their art — well that’s just western bourgeoise rationalism. No room for that here, in the precincts of the great conspiracy known as contemporary art.

Such is Lagrange Point’s great success and its utter failure: it’s a curatorial conceit and discourse that is so far up its own ass as to make evidently ambitious works (some of them anyway) nothing more than props in yet another take on the great simulation in which we all live and which some of us, Ninth Planet for example, believe we can “other-ways-of-know” ourselves out of.

One is tempted to think of it as some Nathan-Fielder-scaled exercise in phosphorescent quotation? But it’s impossible to know. So let the conspiracy continue.2

Tyler Ormsby at Altman Siegel

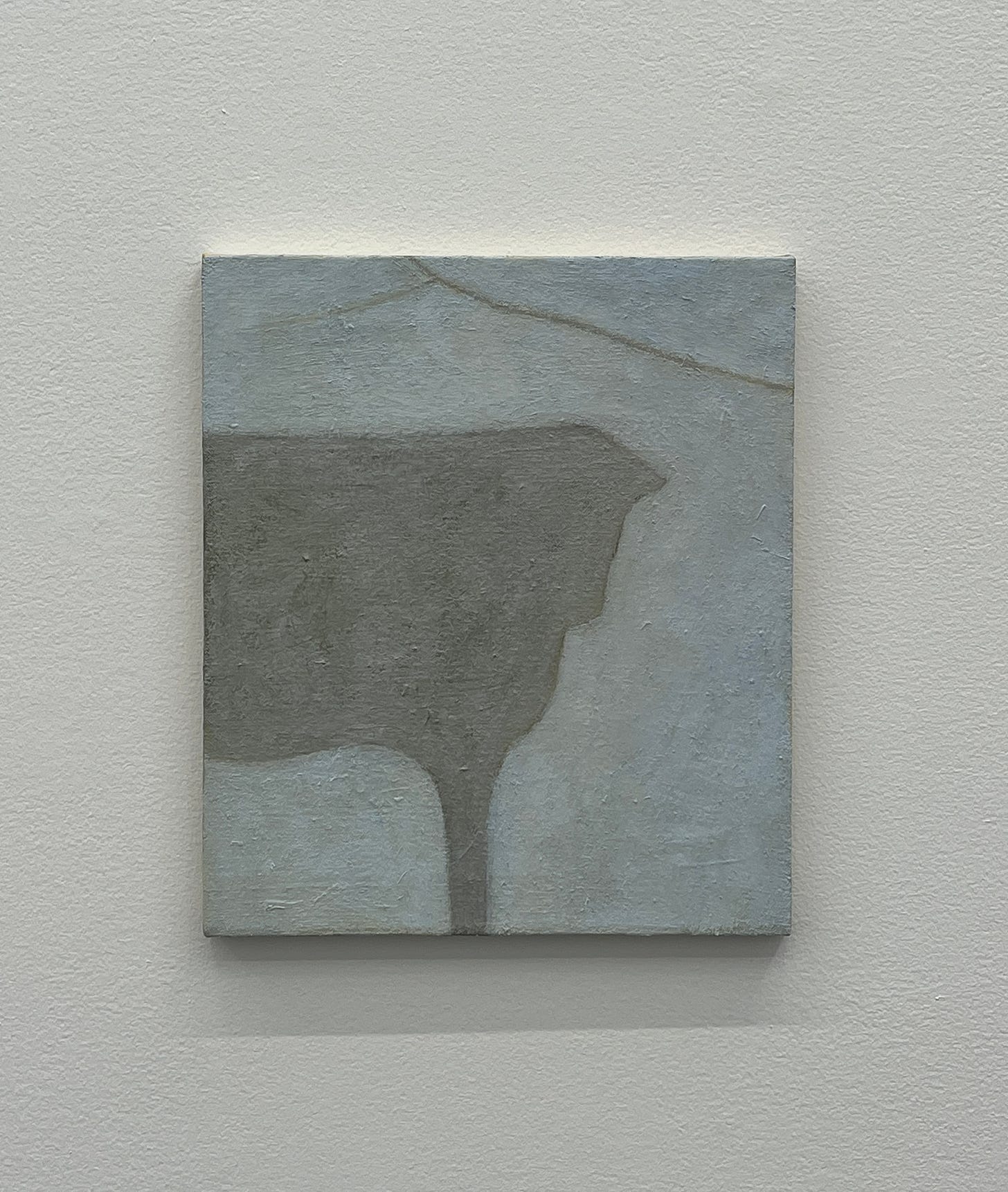

Ormsby’s paintings do something very difficult to do, at least to me, and that is force a double-take. They play with the limits of legibility in a way that other artists have attempted, and achieved, in more conceptual or material and self-conscious ways — I’m thinking here of someone like Gedi Sibony — but do so with an extreme economy of gesture and form, in modest paintings, of modest size and simple subjects.

For example, my immediate first association with Punk leaf (2025) was that it is a picture of cow (I know, I know, bear with me).3 It’s a quick registration, given exclusively by the silhouette. That it’s plainly an animal subject is confirmed by Fuzz (2025), which is larger and features the full figure and thus makes the bovine case explicit. But attend for a moment to the line of the head. My very distinct first impression was that this is a silhoutte of the animal looking at us, and so the edge of the head is one formed by what would be the animal’s left ear and the left side of its face. (The right side would be overlapping with its body and thus invisible in silhouette.) I got this impression from both pictures and left it at that for a moment.

And then I looked again, and though that first impression of the cow turning its head to look in our direction was still there, I now also saw it looking down, such that the silhouette would be capturing the bridge of the animal’s nose and its ears overlapping and pointing forward. And then quickly, it was looking away, formally the same as my first impression, but distinctively different in what I thought I was seeing. After which, like a word repeated so often that its sound becomes impossibly strange to the speaker, the painting just dissolves into an oddity of form and texture.

The other works in this small presentation function in the same way. The compositions seem designed to offer an initial quick recognition, and then to just as quickly challenge that first take with a second (and third, and forth, and so on…). I’m tempted to call it a form game that is about recognition itself.4 But a game that also accounts for the speed of looking, and concluding, that is so prevalent today. (Images want us registering content as quickly as possible; they aspire to pure signal, bereft of noise.). And instead of indulging in the cliche of “slowing down” our perception, Ormsby’s canvases acknowledge that speed, and accommodate it. They are distillations that verge on the edge of disintegration. The longer they hold your attention, the less recognizable they become.

The larger works in the show begin to lose this dynamic somewhat, though hold to it in places — start with the “legs” in Bar room scene (2025), then move to the shoulders, and then the odd half “mandorla” that hugs the figure’s left side. This work called to mind the central figure of Seurat’s Parade de Cirque (1888), perhaps the most important picture about sustained and dispersed “attention” in the modern period.5 At any rate, the question is whether this form game is really one that Ormsby is playing. It’s not the type of work I normally go in for, but it caught me out and made me look again, and that deserves recognition.

On Issac Julien

I have seen Isaac Julien’s Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022) three times: at the Tate, at the Whitney, and now at the de Young, where it anchors the artist’s newest survey exhibition. It’s Julien’s best work, though Lessons of the Hour (2019), Julien’s twelve-channel ode to American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, comes very close.

But Once Again is best because it is also Julien’s last—“last” in the sense that, yes, it’s his latest major work, but also “last” in the sense that it would seem to mark the closure to a period of Julien’s artistic production. We can think about this as the closure of a period of “moving-image” work that once went by the name of “video,” a period of aesthetics and politics that was primarily concerned with the identities of peoples and mediums, especially as these could be shown to be overdetermined by institutions and disciplines, which video’s penchant for the multi-screen installation often modeled. In this, Once Again is a consummate work of video art, but a work that speaks to the form’s beginnings and ends. So what I want to say is that Once Again is the last work of video art that any of us will ever see, and Julien, The Last Video Artist…

Read the rest at e-Flux Criticism

Hugh Kenner, The Counterfeiters: An Historical Comedy (1968). I would recommend Kenner’s short study to anyone today who frets about our “post-truth” moment and believes that we are on the cusp of a frontier, demarcated by AI, beyond which a “shared reality” will be history. Such anxieties are not new. In fact, they are as old as modernity itself.

I need to be clear that this is not one of those it’s-so-bad-it-might-be-good takes. What is good about this show, some of the work in it, and the curatorial conceit itself, is its ambition: the obvious sense one gets that the artists have taken great care to make work and to present it in the form of an argument. Ninth Planet have a position, on how the world works and how art works and how the two might intersect. They are trying to articulate that position. The work, for better or worse, takes part in that articulation. That effort, at least, is to be lauded. That they can fail so wildly in their efforts at compelling any kind of conviction as to the necessity or veracity or import of their argument — for their art, or for art in general — is a testament to their having taken the shot. I do find myself looking forward to seeing work from some of these artists again, but in some entirely different simulation, and probably one in which I’m not me.

And yes, the thought that attended that first registration was “Oh, for fuck’s sake, really?” But it’s Ormsby’s achievement to solicit such an initial response and then convince you otherwise.

I wrote about this in Leon Kossoff’s work: See my “The Freedom to Recognize a Face”

Required reading here is Jonathan Crary’s chapter on this work in his Suspensions of Perception (MIT, 2001).