Fashioning an "American Sublime": Amy Sherald at SFMOMA

The celebrated painter of First Lady Michelle Obama may not really be a portraitist after all.

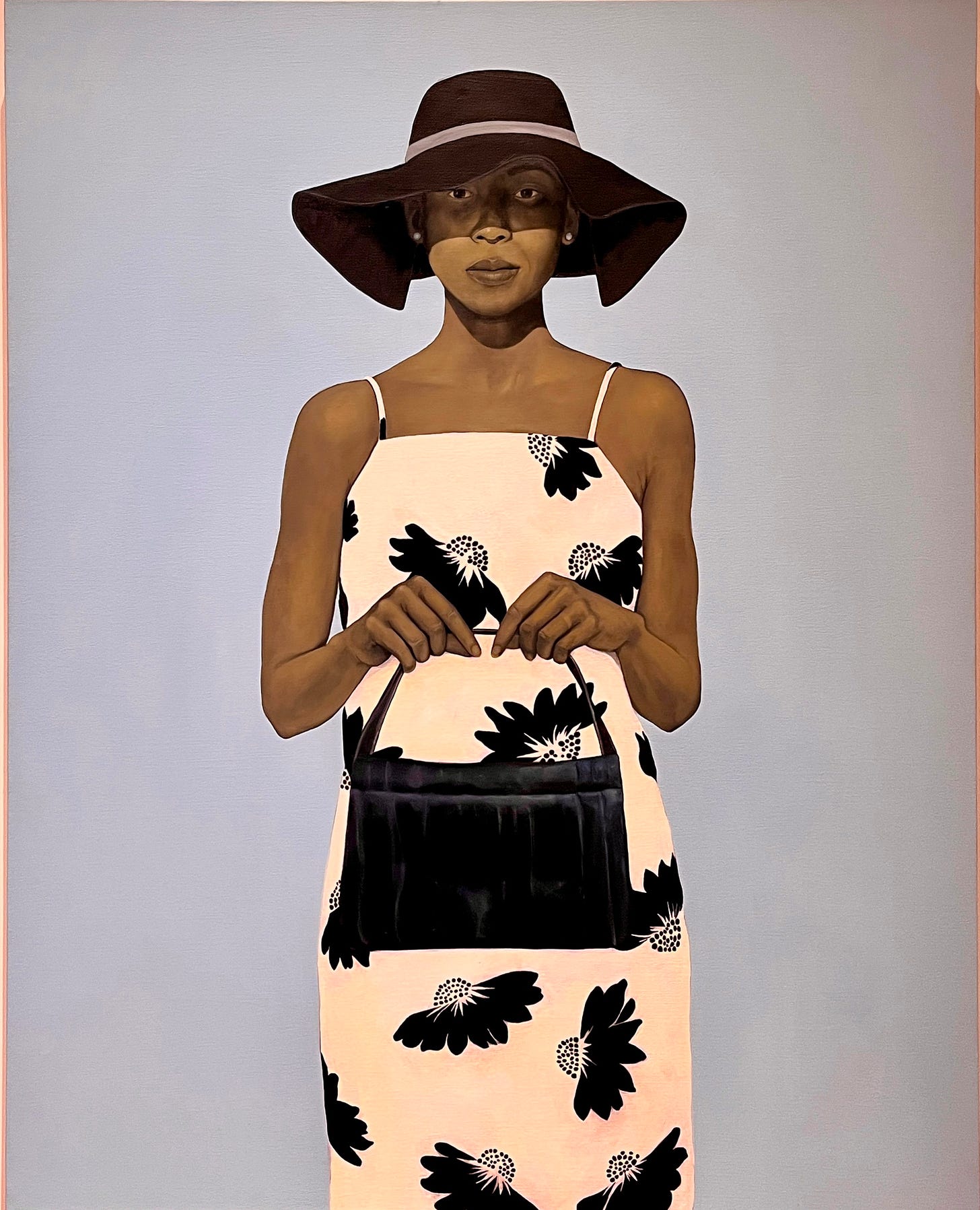

Would it be impolitic to say that Amy Sherald is a painter of clothing, of fashion, and not of people, or portraits? As much as she is known as a portraitist, and her paintings of Michelle Obama and Breonna Taylor have been canonized — the former as a shake-up of the conventions of staid political aggrandizement; the latter as a conventional attempt at aggrandizing a victim of capricious state violence — almost everything offered in Amy Sherald: American Sublime at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (the first major survey of her work, which is next traveling to the Whitney Museum in New York and the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C.) suggests she has been more interested in how clothes look than how people do. To put it simply, she is a painter of models, and their fashions, more than she is of people, and their personas.

Of course portraiture has always been to a certain extent about the sitter’s self-fashioning, and the artist’s fashioning of the sitter’s image. It often has as much to do with what the subjects are wearing — think Sargent’s Madame X — as with how the subjects themselves look: the looks they have and give. But to accept that what Sherald is doing is closer in nature to something like amateur fashion photography — and that this may not be a bad thing — would certainly deflate the grandiose claims that are made about her work as portraits.

For example, Sarah Roberts, the show’s curator, announces that, “by creating images of Black men, women and children at ease, with few markers of place, time or context beyond the clothes they wear, Sherald has invented an entirely new form of figurative painting.” Would that this were so.

One could simply wave a hand and dismiss this as hyperbolic PR copy — and of course it is that. But it is also what a more and less informed public is being asked to accept about Sherald’s work. That Sherald “has invented an entirely new form of figurative painting” is on its face an absurd claim to make about works that so closely resemble and follow in the footsteps of paintings by artists such as Barkley L. Hendricks, one of Sherald’s acknowledged influences. And yet the painter that most comes to mind when looking at the collected works in American Sublime is Alex Katz, but this goes largely unmentioned in most of the public-facing writing about her work. If Sherald’s flat graphic technique doesn’t owe as much to Katz’s eight decades of simmered figures and chromatic reductions as it does to Hendricks or even Kerry James Marshall, I’m not sure what “championing a more expansive history of art” — SFMOMA’s mission according to its director Christopher Bedford — is for.

Roberts also notes that Sherald’s “paintings invite viewers to recognize and move beyond preconceived ideas and engage in more expansive thinking about race, representation and the wide-open possibilities and complexities of every individual.” Taken as a whole, one does see the figures in American Sublime as distinct people, but whatever complexity they may evince is a function of what they are shown wearing, and in certain cases what they are pictured with, rather than how they, as individuals, actually look. The one very received idea that American Sublime doesn’t come close to moving beyond with regard to race and representation is the well-worn connection between Black identity and sartorial style. For the majority of the work in the exhibition, it is quite literally the clothes that make the person, and the painting.

Sherald’s headline-making portrait of Michelle Obama, wearing a dress by Milly designer Michelle Smith, is only the most obvious example here. When the painting was first presented, even the critics most inclined to celebrate the work couldn’t help remarking upon the fact that the face it presented doesn’t look like Michelle’s, but these observations were quickly and energetically discounted in favor of what is taken to be the work’s “bold” departure from the conventions of portraiture, political, celebrity, and otherwise.

Shunning the convention of resemblance is itself highly conventional of course. From Picasso’s Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1906) through to Rauschenberg’s This is a Portrait of Iris Clert if I Say So (1961), resemblance in portraiture was indeed demonstrated over the course of the Twentieth Century to be just that, a convention, one that could be toyed with or tossed out. It was exactly the relationship of identity that no longer held, a relationship that resemblance was thought to secure. To hold that “this is a picture of that” required nothing so much as a statement to that fact. Rauschenberg issued that statement using a telegram. Sherald and Obama used a press conference.

If I were going to make an argument for Sherald’s portrait, it would be that this relationship of resemblance, the thing that secures the identity of the subject — who this is a picture of — is secured only for what Obama is wearing. This may sound like a trivial point to make, but the dress comprises at least half of the painted surface of the picture. And the cut and the pattern announce that this clothing has been authored, and by someone self-consciously aware of histories of art and craft, with their parallel and sometimes dueling legacies of geometric abstraction. In other words, it is an “art” dress. And so if Obama is wearing someone, the portrait is as much if not more a picture of that something, not just because there is more of it but because the more of it that is there makes it highly identifiable both as fashion and as art.

Put slightly differently, the question of “Who is she wearing?” is just as important as the question of “Who is that?” And given the tenuous relationship of resemblance that the painting holds to its sitter, the question of identity here becomes one of identifiability, which is more easily answered in the first case (she is wearing “Michelle Smith for Milly”) than it is in the second (she is Michelle Obama).

Such an account would make this a more interesting picture than I think it actually is, however, insofar as it’s not clear that Sherald herself is interested in this exchange of identity for identifiability, particularly in the case of a “power portrait” of a former First Lady of the United States. Did Sherald intend for this picture to stretch the limits of Obama’s identifiability? It’s not clear, and that’s not exactly good.

Sherald’s portrait of Breonna Taylor, which enacts for Taylor a self-composed dignity that she was denied in life, offers the obvious counterexample. No playful fashion identifiability here. Just responsible resemblance, composure as a function of composition, and no mistaking who it is a picture of.

When the people in Sherald’s paintings are not public figures, as are the majority of the subjects we see in American Sublime, what one is mostly left with is what the figures are wearing. From the standpoint of how the subjects are dressed, it’s fashion portraiture, or fashion picturing, as I want to say, because portraiture presumes a subject, and Sherald does not give us access to any subjectivity. Perhaps this is by design. But if it is, what Sherald is making is more like anti-portraiture, if one might call it that, a challenge to anything like the “complexity of individuals” that the show wants to celebrate and which an exhibition of portraiture could be expected to deliver.

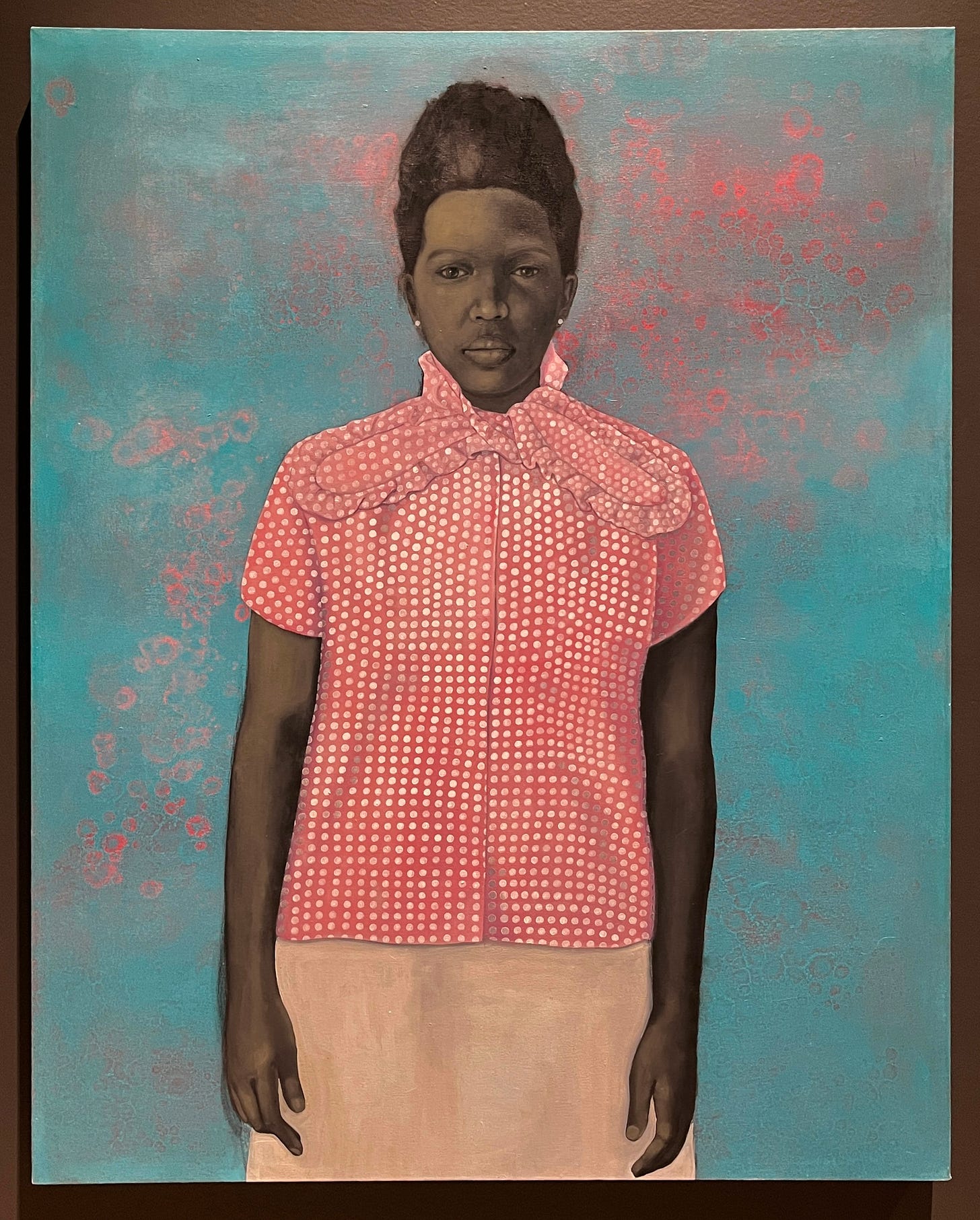

On the evidence of the earliest canvases in American Sublime, Sherald wasn’t always committed to this direction. Well Prepared and Maladjusted (2008) is explained to the viewer (via a wall label) as one of the first in which the artist “uses gray for skin tone” and where the “subject faces the viewer directly” as a means of staging a conflict or tension between the subject’s “inner life” and the outward sign of her “race” — a conflict that is given as central to Sherald’s entire project. That the subject in Well Prepared is a person, is rendered with enough fidelity to the particularities of an individual such that we can presume her to be one (and not an invented composite or synthesis, as in the work of Thomas J. Price), does not by itself grant us access to something like the subject’s “inner life” or mind.

That she may have an inner life can be assumed, but that assumption comes with the most minimal recognition of the subject as another human being. There is nothing in this figure’s pose, or look, nothing in the body’s gesture or stance, nothing in the face or its lack of expression, that would give us a sense of what that inner life actually is. And without any content, is there any value in ascribing an inner life to the subject at all?

Another way of putting this would be simply to state that the question “What is she thinking?” is both unanswerable and trivial, because it’s not a question that the artist appears to have been interested in either. Look at the handling of the background, with it’s eruptions of droplets that shade from pinks into reds on a worked-over turquoise ground. Look at the modeling of the skin and how the beige of the skirt pushes against and defines the thumb of the figure’s right hand while holding or beginning to envelope the thumb of the left hand. Look at the difficulty with which the creases of the blouse and the pleats of its collar are worked out against the pattern of its polkadots. These are problems of painting, not fashion, or even self-fashioning, which Sherald is taking seriously in 2008. Though the clothes are prominent, there is no sense in which they are primary — that is, the thing that the picture is about. How painting is going to serve the question of portraiture is here still an open question.

In contrast, on the wall just next to Well Prepared is hung To Tell Her Story You Must Walk in Her Shoes, a much more recent work (from 2022), in which the clothing is primary, is, in some sense, just what the work is about. It’s not for nothing that the earnestness of the title is offset by the wink one gets from the image on the subject’s sweater. But entirely gone from To Tell Her Story are the painting problems that she began working through prior and up to around 2008. This is the flat, graphic idiom of Katz, but one in which fashion takes over from figure, and posing is mistaken for portraiture.

A pictorial project about fashion as a formal problem that painting has to solve could be interesting. But for my part, the best paintings in the show are the ones that depart from any suggestion of that problem by exchanging fashions for things, which her subjects, the sitters, adorn, instead of hold or wear themselves. For example, if a A God Blessed Land (Empire of Dirt) (2022) can be said to be a portrait of anything, it’s of a beautiful, and beautifully rendered, yellow and green John Deere 820 tractor. Of course it’s important that on the tractor is posed a man sporting clean blue-jean overalls and a bright white t-shirt. With one leg resting on the massive back wheel of the rig, allowing him to lean forward with his arms crossed on raised knee, Sherald’s “farmer” is only missing a sprig of straw between his teeth to complete the cliche.

For some, it will be important that the farmer is black, pointing as this will, for many, to an entire history of slavery and sharecropping, to “40 acres and a mule,” and to the special relationship that many Black Americans have to the land that has made the United States the unique State that it is. But if that man, Sherald’s farmer, is doing anything in the picture, he’s posing with that tractor — he’s selling it, as a model, not as a subject (would it even matter if the tractor were in fact his?). Perhaps he is a subject, a sitter, but from the look of the painting, and the way that Sherald has rendered it, do we really care? The tractor is the figure, the subject (no interiority, pure object); the man is its ornament, like the earrings or the snake pin in To Tell Her Story (no interiority, all surface). He is, in short, an accessory. And as such, with a work like A God Blessed Land, the transformation from portrait painting to fashion picturing (even to product placement) is, I would say, complete.

The question that I now feel compelled to ask is this: Regarding Sherald’s work and the way that it is being posed to the public, were her subjects always accessories? No deep sensibility, no internal life, no affirmation of even a group identity, except for however one might be identifiable — not fashioned by the subjects, but rather simply styled by the artist? I don’t know the answer to that. But to my eye it makes Sherald’s project more interesting, but I suspect it’s not what Sherald or Roberts or SFMOMA or even most visitors will have in mind when they consider whatever an American Sublime might be.

Interesting examination, Jonathan. Sounds like a great show, actually. I have always placed Sherald's work in my art brain as one of a number of contemporary Black painters who are actively decolonizing portraiture as a form. Perhaps the most obvious, Titus Kaphar and Kehinde Wiley. I would also include Jordan Casteel, Deborah Roberts, and Daisy Patton in that group, among others. It is what made the choices of Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald so monumentally appropriate for the portraits of the first Black American President and First Lady. And I think what you say about costume and fashion is very much part of that process. To me, and I think in these works, clothing is not just drape. It is identity, agency, and humanity. Especially in the long history of Black experience in this country. In colonial and early American depictions, painters of Black people typically portrayed them in traditional dress of white people (assimilative), or as poorly clad property (objectified). Fabric itself is a part of Black historical identity, as exemplified in Bisa Butler's portraiture, or the African textile-inspired backgrounds and draping in Kehinde Wiley's works. They are the opposite of traditional Western portraiture, which is often very somber and dark, while largely being the purview of an elite class. The details you mention about the dress in Sherald's portraits seem subtle, but as important as facial expression in conveying interiority of these subjects. Even the piece in which the tractor dominates the field, the tractor and the overalls, and the title of the work itself, speak to agency and identity of that particular Black farmer in America, an often overlooked group in the annals of American farming. As for Michelle, she is stunning as always in Sherald's depiction. I have a print of that work on my office wall. The pattern of the fabric is a contemporary homage to African roots, while the style and posture represent her as a contemporary scion of powerful grace. Verisimilitude is perhaps the least important part of that work. Think of how many different likenesses there are of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, and we still recognize them on site, never knowing which one is most accurate.

Thanks for the fun brain exercise. I love hearing your takes on the art world!