Faith Ringgold's Freedoms

What do we miss when we see Faith Ringgold's work only in black and white?

I wrote the piece below after a trip to Chicago to see Faith Ringgold: American People when it opened at the MCA Chicago last November. The trip was generously underwritten by the museum and overseen by an outside PR team with an expectation of some sort of coverage running in one of the magazines to which I semi-regularly contribute. I submitted the piece on deadline, but as sometimes happens in publishing, it got pushed aside, dragged out — never officially killed but put out to pasture. A motto that governs my thoughts about the writing-editing-publishing sequence is “hold on tightly; let go lightly” (whether I got this from a John Denver lyric or Clive Owen in The Croupier [1997] I can’t recall; both thoughts make me cringe a bit). Take the writing seriously. Work at it. Be honest. Try for something. But once it’s out of your hands, get your ego out of the way. Once it’s in the wild, anything can happen — killed, maimed, captured, brainwashed, body-snatched, impersonated; but also cared about, shared, considered and incorporated. You can’t control it, so don’t try. Just write again. At any rate, I’m posting it here so that it can breath at least a little wild air.

When American People, the extensive survey of Faith Ringgold’s art from the 1960s to the 2000s, debuted at The New Museum in February 2022, the United States was still in the throes of a “racial reckoning” after the murder of George Floyd. Identity consciousness, very much on the rise in the first quarter of this century, came to dominate the art world. Headlines exclaimed Ringgold’s “critique of racist America” to be “as relevant as ever” (The Guardian). Her work was repeatedly framed as “relentlessly challenging social hierarchies, racial prejudice and gender norms” while “continuing to shed light on social justice and identity issues” (The Art Newspaper). Hers was a path of “maximum resistance” (The New York Times) against a racist art world that had “ignored Faith Ringgold for decades” (Artnet).

My question is this: does this context, does this identity consciousness, do justice to Ringgold’s art?

Throughout her career, Ringgold has been without a doubt an activist committed to the struggles for equal rights and opportunities for Black Americans and women. Her work is explicit about this. But it is also at times ambivalent about it, and even complicates those commitments through its formal and narrative experiments. Yet critics have often ignored Ringgold’s own work and words in order to perpetuate narrow, identity-driven readings of her art.

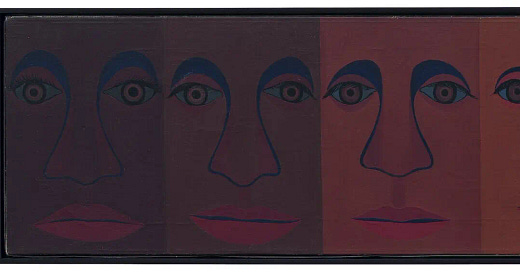

Take, as an example, the Black Light Series paintings which Ringgold began in 1967. In these works, Ringgold initiated new experiments with what she calls the “mask face.” These canvases combine, according to Ringgold, “African design with modern serial art concepts,” and use block-lettered words, including Ringgold’s own name, as “posterlike elements of design.” Black Light Series #9: The American Spectrum (1969) (pictured above), which shows six tightly cropped mask faces in different shades of brown – Ringgold called it a “subtle statement of black people’s multiethnic heritage” – was sold from her second solo show at the Spectrum Gallery in 1970 to David Rockeller’s Chase Manhattan Bank collection. The price was $3000 (roughly $24,000 in today’s dollars). In Ringgold’s own words, a “formidable sale.”

For most commenters on the Black Light Series, however, only one detail seems salient: Charles Moore, writing in The Art Newspaper, tells us that it “omits the colour white.” Beau Rutland, writing in ArtForum, states that the Black Light Series is “marked by Ringgold’s decision to forgo the use of white paint.” “For a group called Black Light Series” – this is Holland Cotter in The New York Times – “Ringgold eliminated white paint entirely from her palette and darkened her colors with black.” Melissa Smith, writing in Artnet, is explicit about the politics of this move, noting how Ringgold, in the late 1960s, “pivoted to her Black Light Series, a group of pieces that included agitprop-style texts and African-inspired portraits with even more overt Black Power messaging, to the point where she eliminated the use of white paint altogether.”

But here is Ringgold in We Flew Over the Bridge, her memoir, first published in 1995:

I made my early black paintings in 1967 by very crudely mixing ivory black into other colors to darken them. Because ivory black has a high oil content, it dries slowly and produces an uneven glossy sheen. Continuing to perfect my new palette, I switched from ivory black to Mars black, which dries faster and has a beautiful matte finish. Then I decided to add burnt umber, which also has a beautiful surface quality and emulates dark flesh tones. I used flake white to create opacity and to lighten my colors a little [emphasis added].

When I read this I had to look up “flake white” to make sure I wasn’t missing something. But as the name says, it’s white paint, and there is Ringgold, in print, in her own words, stating that she used it for this series. Nowhere in her autobiography does Ringgold write that the color white was “omitted,” “forgone,” or “eliminated” as some symbolic act in the service of a her, or anyone else’s, politics.

Of course the Black Light Series has a politics to it, a politics that issues from the Black Power and Black is Beautiful messaging of its moment, but the passage above not only demonstrates that a broad cohort of estimable art writers are perpetuating both a factual and a critical falsehood about Ringgold’s art – bad enough on its own! – the passage is also, and perhaps more importantly, just a slice of an extended meditation on the use of black hues in European and African Art, a meditation in which Ringgold name checks Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, and Massacio, and demonstrates an acute understanding of how color theory is at work in her art – all of which goes unnoted and unrecognized when wanting to read Ringgold’s art as emblematic of a black and white, of a black vs. white, racial dynamic.

There is no justice in this. The great essayist and critic Albert Murray, writing at the same time that Ringgold was making these works, would no doubt chalk this up to the persistence of a “folklore of white supremacy and the fakelore of black pathology.” As Murray would put it in The Omni-Americans (1970): “Indeed, for all their traditional antagonisms and obvious differences, the so-called black and so-called white people of the United States resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other. And what is more, even their most extreme and violent polarities represent nothing so much as the natural history of pluralism in an open society.” Ringgold’s newly iconic American People #20: Die (1967) is, if anything, a perfect, and perfectly graphic, illustration of Murray’s position.

Another example: Ringgold’s The French Collection Part I (1989-91) tells a story, serialized in pictures and text across eight quilts, of Willia Marie Simone who, in the 1920s, travels to Paris to become an artist, marries a wealthy white man, has two children, and becomes part of the Parisian avant-garde, painting a gathering of feminists at Giverny (including a nude Picasso in a pose that quotes Edouard Manet’s Dejeuner sur l’herbe), modeling for Matisse and Picasso (as an addition to the latter’s Demoiselles D’Avignon), and piecing a quilt of sunflowers in Arles with female icons from the history of Black American liberation – Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Ida Wells, and others – while Van Gogh looks on.

When looking at and reading these works, one can be sure that Willia Marie’s identity as a Black American woman is central to the series, but it’s an identity that is often at odds with her sense of herself as an artist, her desire to “paint something that will inspire – liberate!” Yet in her otherwise illuminating essay on The French Collection, Michele Wallace writes that here “Faith rearranges history and location to include people, places, and events that did not and could not have shared the same context, to underscore the relevance of race and gender to her project.”

Forgive me, because here I know I am about to argue against the writer and thinker who has an indisputable claim to knowing Ringgold best – her daughter! – but it does not hold for me that Ringgold’s inventive foldings of time and place, her imagined encounters between historical and fictional figures, are meant to “underscore the relevance of race and gender.” If these moves underscore anything it is the project of liberation, of freedom, which in Ringgold’s project is synonymous with art and entails, crucially, what one is willing to sacrifice for it.

It cannot be of only passing significance that in the final quilt of the series, On the Beach in St. Tropez, we see Willia Marie settled comfortably in a breezy vacation scene, but also learn that she had long ago sent her children to be raised by her sister in Georgia. As Willia Marie says in the second quilt of the series: “I want to live a life of making art, not babies and dinner and beds.”

Recall now that this is the 1920s, and dwell on this for a moment: In order to pursue her art, and her self-fulfillment as an artist, which, in the story, is never fully achieved, is always ambivalently asserted, Willia Marie sends her children to come of age in Georgia, in the heart of Jim Crow America, in a stronghold of the KKK. If race and gender are relevant, then they are only relevant insofar as they serve to illustrate the depths of the sacrifice that one must make for one’s freedom, for one’s art. Race and gender are not the project. Freedom is.

Willia Marie’s story is fictional of course. No matter how loosely or strongly based on Ringgold, or Ringgold’s mother the character of Wilia Marie actually is, she is a character, an artifice, a vehicle, like the painting, like the quilting, through which Ringgold is making art and taking liberties – claiming liberty for herself. To make art is to be free, and freedom demands sacrifice, it demands commitment, it demands more than identity consciousness can hope to deliver. And as Ringgold makes abundantly clear, for American People, but not only for American People, the stakes are high.